Raghuram Rajan says there were better options than demonetisation

Sun 03 Sep 2017, 19:21:38

Former RBI governor Raghuram Rajan has revealed that he did not favour demonetisation as he felt the short term economic costs associated with such a disruptive decision would outweigh any longer term benefits from it.

Rajan makes the disclosure in his latest book - I do what I do - which is a compilation of speeches he delivered on wide range of issues as the RBI governor. Although he maintains the book is not a tell-all, the short introductions and postscripts accompanying the pieces offer fascinating insights into his uneasy relationship and differences with the present government.

"At no point during my term was the RBI asked to make a decision on demonetisation," Rajan has said, putting to rest speculation that preparations for scrapping high-value banknotes got underway many months before Prime Minister Narendra Modi made the surprise announcement on November 8.

This is the first time the former RBI governor has spoken on demonetisation since demitting office on September 3 last year. Rajan, who now teaches economics at University of Chicago, said he chose not to speak on India for a year because he didn't want to "intrude on his successor's initial engagement with the public".

"I was asked by the government in February 2016 for my view on demonetisation, which I gave orally. Although there might be long-term benefits, I felt the likely short-term economic costs would outweigh them," Rajan wrote.

"I made these views known in no uncertain terms."

He didn't elaborate on the short-term costs or the possible long-term benefits, but as the RBI governor he "felt there were alternatives to achieve the main goals."

Latest government data showed the November 8 decision to scrap Rs 1,000 and Rs 500 notes, sucking out 86% of cash circulating in the system, has had a lingering impact on the economy.

The growth of GDP slowed sharply from 7% in October-December quarter to 6.1% in January-March and 5.7% in April-June, primarily because of the cash squeeze that weakened consumer spending and discouraged businesses from making new investments.

The government, however, maintains that the economic slowdown has not been entirely because of demonetisation. In an interview to Times of India, published Sunday, Rajan described the deceleration in GDP as "the costs of demonetisation upfront."

"Let us not mince words about it - GDP suffered. The estimates I have seen range from 1 to 2 percentage points, and

that's a lot of money - over Rs 2 lakh crore and may be approaching Rs 2.5 lakh crore," he said in the interview.

that's a lot of money - over Rs 2 lakh crore and may be approaching Rs 2.5 lakh crore," he said in the interview.

"I think the people who mooted this must have thought some of it would be compensated if money didn't come back into the system," he said referring to illegal wealth held in cash.

The government's expectation was that at least Rs 3 lakh crore worth black money held in cash won't return, significantly reducing the liability of the central bank and boosting its profits, which could be used for new investments and developmental work.

But RBI data, available now, shows 99% of the high-value notes have returned to the banking system, meaning hoarders of black money found a way to legitimise most of their dodgy cash.

"The fact that 99% has been deposited certainly does suggest that aim (of curbing black money) has not been met," Rajan said in the interview.

Despite his reservations, Rajan wrote in his book, the RBI was asked to prepare a note, which it did and handed to the government.

The RBI note, he said, "outlined potential costs and benefits of demonetisation, as well as alternatives that could achieve similar aims. If the government, on weighing the pros and cons, still decided to go ahead with demonetisation, the note outlined the preparation that would be needed, and the time that preparation would take."

"The RBI flagged what would happen if preparation was inadequate," he wrote.

The government subsequently set up a committee to consider the issue. The central bank was represented on the committee by its deputy governor in charge of currency, Rajan wrote, possibly implying he did not attend these meetings.

The current leadership of the central bank could not be reached for comments on Rajan's account. Phone calls to the RBI spokesperson went unanswered.

Rajan did not detail the contents of the note RBI had submitted to the government. Modi's radical move was slammed by the opposition as ill-conceived and poorly executed. It took banks much longer than the government had expected to tide over the cash crisis. Frequent changes in cash withdrawal rules added to chaos and inconvenience that lasted far longer than the 50 days the PM had sought to restore normalcy.

Still, Modi won popular support for his move, winning a landslide victory in crucial elections in Uttar Pradesh. Most people, especially the poor, backed his decision as a frontal attack on black money.

No Comments For This Post, Be first to write a Comment.

Most viewed from Business

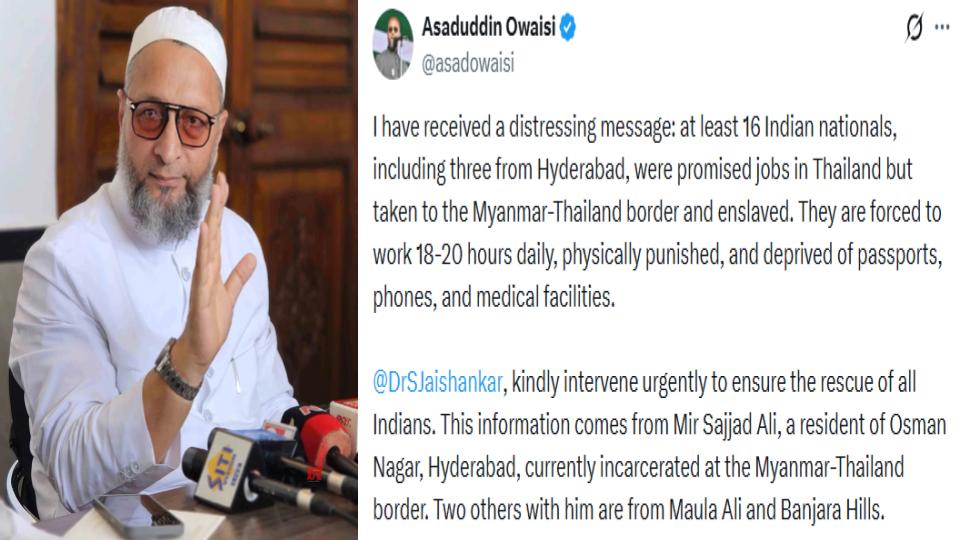

AIMIM News

Latest Urdu News

Most Viewed

May 26, 2020

Should there be an India-Pakistan cricket match or not?

Latest Videos View All

Like Us

Home

About Us

Advertise With Us

All Polls

Epaper Archives

Privacy Policy

Contact Us

Download Etemaad App

© 2026 Etemaad Daily News, All Rights Reserved.

.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)