'Padmaavat' movie review: An embarrassing cultural aesthetic all of us could have done without

Fri 26 Jan 2018, 20:22:56

Director: Sanjay Leela Bhansali

Cast: Deepika Padukone, Ranveer Singh, Shahid Kapoor

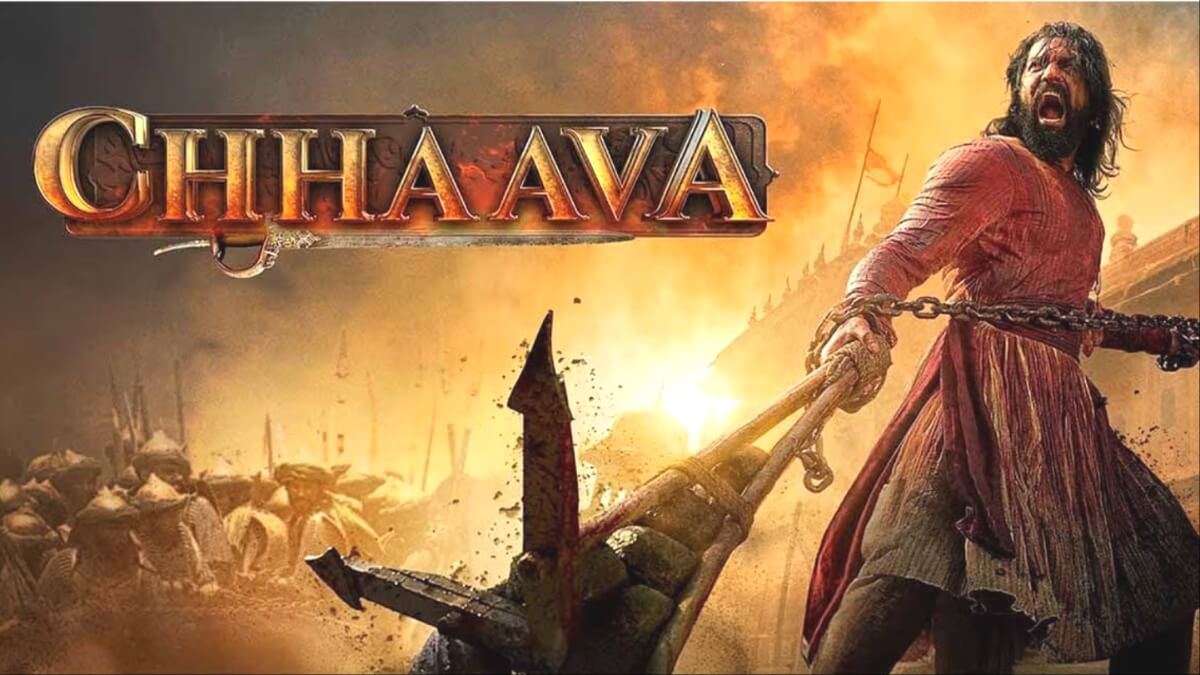

The big controversial movie is finally out. Sanjay Leela Bhansali’s Padmavati, rechristened as Padmaavat, makes it to the big screens this week even as calls for the ban are still ringing. After committee after committee was formed to evaluate the film, censor the film, find out if it is offensive to everyone from the Rajputs to Rani Padmini’s (who is a figment of imagination, by the way) first cousin twice removed, the film releases after a handful of cuts and modifications.

Adapted from Malik Muhammad Jayasi’s 16th century poem Padmavat, everything you need to know about the film is out there and has been playing in front of your television screens, phones, WhatsApp and social media for the last two months. What you did not know, however, is that the Karni Sena — the safe-guarders of Rajputs’ culture, women, practices like jauhar — are likely to break into a standing ovation by the time Sanjay Leela Bhansali’s name appears on screen. Or did you?

Padmavati (Deepika Padukone) gets an introduction very similar to the one the Rajput princess—Mastani—got in Bhansali’s earlier film, Bajirao Mastani. We see her hunting in the woods, swords exchanged for bow & arrows, when, as part of Bhansali’s inescapable symbolism, she makes a mark on Ratan Singh (Shahid Kapoor) of Mewar. In both the films, it is Bhansali’s muse who gets the bigger introduction, the heroes can only dream of such a sequence.

But unintentionally or by design, Bhansali loves to introduce his women in all their feisty glory and then pull the agency from under their feet. Not that the roles they go on to inhabit fail to service the film, but these introductions exist in vacuum, they are mere set pieces and the one in Bajirao Mastani turns out to be more organic in retrospect.

One can, of course, argue that Bhansali’s films are clever, elaborate set pieces themselves, but Padmaavat will probably go down as one of his weakest films. There is a lot of dead air and Deepika Padukone is — as unforgivable as this is — given precious little to work with. Padmaavat therefore becomes more about Alauddin Khilji (Ranveer Singh)—reigning over Delhi Sultanate—who establishes a watchtower outside Chittor in his

obsession with Padmavati.

obsession with Padmavati.

Bhansali throws everything at you. With a Muslim king pitching tent outside the Helm’s Deep of Rajputs, he has the Chittor populace celebrating everything from Diwali to Holi, but still fails to repeat the magic of that scene in Bajirao Mastani when Bajirao returns from war and an exquisite Albela Sajan washes over a range of colours and hues.

Alauddin is depicted like a ghost, his garments oversize, his hair unkempt, and when he gallops into battle, he brings the dust storm with him. He disappears into one and appears out of it with a head mounted on his spear. And that is what he expects with Padmavati too—to bring a dust storm into Chittor and walk away with the queen. A dust storm does occur when his hopes are all dashed, and he returns to Delhi, not with Padmavati but with Ratan Singh. At this point, Padmaavat plays out like a gender reversed Helen of Troy saga between the Greeks and the Trojans. It is also the point when you no longer care.

You no longer care that the gravitas one usually associates with a Bhansali film — the star-crossed lovers, the mise en scene- has spectacularly gone missing. The stakes are never high on screen—an anti-climax to the off-screen din all these months. You no longer care that Bhansali does nothing with the character of Malik Kafur (Jim Sarbh), Khilji’s eunuch-general—the homosexual undertones only alluded to, ever so lightly. You no longer care that Jim Sarbh hasn’t yet built on the promise of Neerja with Padmaavat and Raabta.

You no longer care that it was a Brahmin who betrayed the Rajputs to Alauddin, committed something amounting to treason, and was invited by Khilji to have his circumcision done. Wonder what the Karni Sena makes of such anti-nationals. You do care about the Brahmin being instructed to bring Alauddin Khilji’s food which would have made for a nice visual.

You no longer care that the Muslim king is not only depicted as uncivilised but is also referred to as Yama — Hindu god of death — in the context of Satyavan-Savitri from Mahabharata, when Padmavati saves Ratan Singh from the jaws of death. For the first time in his long career, a Sanjay Leela Bhansali film comes across as superficial, a mere costume extravaganza. An embarrassing cultural aesthetic that all of us could have done without.

No Comments For This Post, Be first to write a Comment.

Most viewed from Film & TV

Most viewed from Entertainment

AIMIM News

Latest Urdu News

Most Viewed

May 26, 2020

Do you think Canada-India relations will improve under New PM Mark Carney?

Latest Videos View All

Like Us

Home

About Us

Advertise With Us

All Polls

Epaper Archives

Privacy Policy

Contact Us

Download Etemaad App

© 2025 Etemaad Daily News, All Rights Reserved.

.jpg)