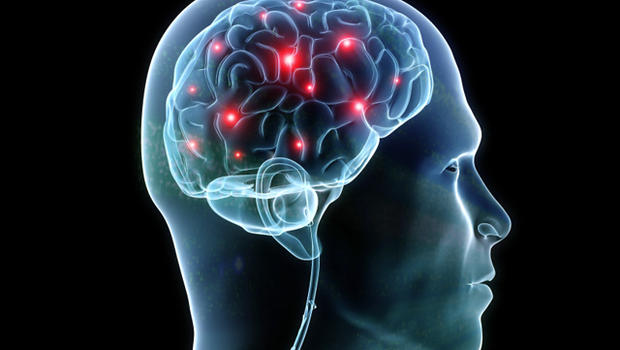

Brain areas that control how we write words decoded

Thu 04 Feb 2016, 12:31:10

By studying stroke victims who have lost the ability to spell, researchers have pinpointed the parts of the brain that control how we write words, shedding new light on the mechanics of language and memory.

For the first time, researchers from Johns Hopkins University in US have linked basic spelling difficulties to seemingly unrelated regions of the brain. Researchers studied 15 years' worth of cases in which 33 people were left with spelling impairments after suffering strokes. Some of the people had long-term memory difficulties, others working-memory issues.

With long-term memory difficulties, people can not remember how to spell words they once knew and tend to make educated guesses.

They could probably correctly guess a predictably spelled word like 'camp,' but with a more unpredictable spelling like 'sauce,' they might try 'soss.' In severe cases, people trying to spell 'lion' might offer things like 'lonp,' 'lint' and even 'tiger.'

With working memory issues, people know how to spell words but they have trouble choosing the correct letters or assembling the letters in

the correct order - 'lion' might be 'liot,' 'lin,' 'lino,' or 'liont.'

the correct order - 'lion' might be 'liot,' 'lin,' 'lino,' or 'liont.'

Researchers used computer mapping to chart the brain lesions of each individual and found that in the long-term memory cases, damage appeared on two areas of the left hemisphere, one towards the front of the brain and the other at the lower part of the brain towards the back.

In working memory cases, the lesions were primarily also in the left hemisphere but in a very different area in the upper part of the brain towards the back. "When something goes wrong with spelling, it is not one thing that always happens - different things can happen and they come from different breakdowns in the brain's machinery," said Brenda Rapp from John Hopkins University.

"I was surprised to see how distant and distinct the brain regions are that support these two subcomponents of the writing process, especially two subcomponents that are so closely inter-related during spelling that some have argued that they shouldn't be thought of as separate functions," Rapp added. The findings were published in the journal Brain.

No Comments For This Post, Be first to write a Comment.

Most viewed from Health

AIMIM News

Latest Urdu News

Most Viewed

May 26, 2020

Which Cricket team will win the IPL 2025 trophy?

Latest Videos View All

Like Us

Home

About Us

Advertise With Us

All Polls

Epaper Archives

Privacy Policy

Contact Us

Download Etemaad App

© 2025 Etemaad Daily News, All Rights Reserved.

.jpg)