New nasal test can help quickly identify asthma in children: Study

Tue 14 Jan 2025, 23:31:12

Asthma is the most common long-term condition in children. According to a recent study, it affects many Black and Puerto Rican children the most.

To help these kids better, new treatments need to be developed. Asthma is usually classified into types called "endotypes" based on the level of inflammation in the body.

The two main types are T2-high (high T2 inflammation) and T2-low (low T2 inflammation). Recently, researchers have further divided T2-low asthma into two groups: T17-high (high T17 inflammation, low T2 inflammation) and low-low (low levels of both T2 and T17 inflammation).

Since asthma can vary greatly from person to person, accurate diagnosis of these endotypes is important for choosing the right treatment. The traditional way to diagnose endotypes involves analysing lung tissue, which requires a procedure called bronchoscopy under general anesthesia.

This method isn't suitable for children, especially those with mild asthma, as it is invasive and risky. Instead, doctors often rely on less accurate methods, like blood tests, lung function tests, and allergy checks.

Now, researchers at the University of Pittsburgh have developed a simple nasal swab test to identify asthma types in children. This non-invasive test could help

doctors provide more accurate treatments and open doors to new therapies for less-studied asthma types.

doctors provide more accurate treatments and open doors to new therapies for less-studied asthma types.

The study, published in JAMA, focused on Puerto Rican and African American children, who have higher asthma rates and are more likely to die from asthma than white children.

The research team analysed nasal swabs from 459 children across three studies. They looked at eight genes linked to T2 and T17 inflammation. The results showed that 23% to 29% of children had T2-high asthma, 35% to 47% had T17-high asthma, and 30% to 38% had low-low asthma.

While medicines targeting T2-high asthma already exist, there are no treatments yet for T17-high and low-low asthma. This new nasal swab test could help scientists focus on developing treatments for these types of asthma and make faster progress in asthma research.

Dr Juan Celed³n, a pediatrician and senior author of the study, highlighted the importance of this breakthrough: "One big question in asthma is why some kids’ asthma worsens during puberty, while others improve or stay the same. Before puberty, asthma is more common in boys, but it’s more common in women as adults. Is this linked to endotype? Does it change over time or with treatment? We don’t know yet, but this new test will help us find answers."

No Comments For This Post, Be first to write a Comment.

Most viewed from Health

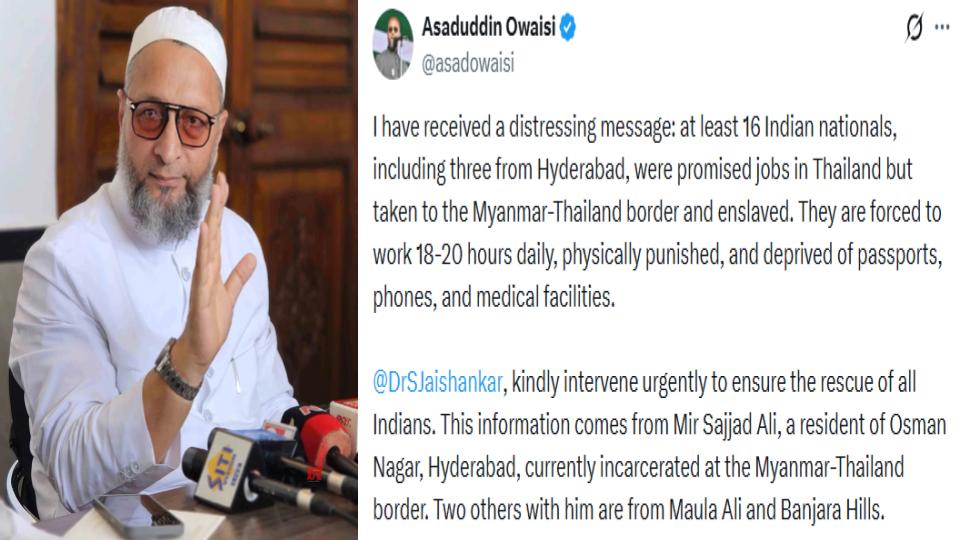

AIMIM News

Latest Urdu News

Most Viewed

May 26, 2020

Is it right to exclude Bangladesh from the T20 World Cup?

Latest Videos View All

Like Us

Home

About Us

Advertise With Us

All Polls

Epaper Archives

Privacy Policy

Contact Us

Download Etemaad App

© 2026 Etemaad Daily News, All Rights Reserved.

.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)