2016 budget deficit ‘to fall below original projection of SR326bn’

Sat 05 Nov 2016, 21:58:43

RIYADH: Saudi Arabia has avoided an economic crisis due to low oil prices this year but the outlook for state finances and growth is likely to remain murky for many months to come, businessmen and analysts in the kingdom say.

Six months after the government launched its most radical economic reforms in decades, it has scored several victories.

Drastic spending cuts seem to be reducing its budget deficit, which totaled a record SR367 billion ($98 billion) last year, by much more than originally planned.

A $17.5 billion sovereign bond issue last month opened an overseas borrowing channel which Riyadh can use to slow the drawdown of its foreign reserves, buying more time to adjust its economy to an era of cheap oil, and for the foreseeable future almost eliminating the risk of a currency devaluation.

The government has accomplished this without any significant political backlash.

While ordinary people grumble at the austerity on social media, many say they understand the need for it, and businessmen praise the authorities’ decisiveness.

But big questions remain.

It is not clear whether the government can continue cutting its deficit rapidly without pushing the country into recession, and many corporate executives think the worst of the economic slump is yet to come.

“Next year there will be high uncertainty, though we do not expect a huge decline,” said Mazen Al-Sudairi, head of research at local firm Al-Istithmar Capital.

“The private sector is facing a lot of challenges.”

A foreign banker in Riyadh agreed the economy had escaped a fiscal and currency crisis that loomed at the start of 2016.

Central bank data shows no sign of rising capital flight from the country, he noted.

“But this does not mean the basic problems are solved,” he said. “Next year will be a very tough year.”

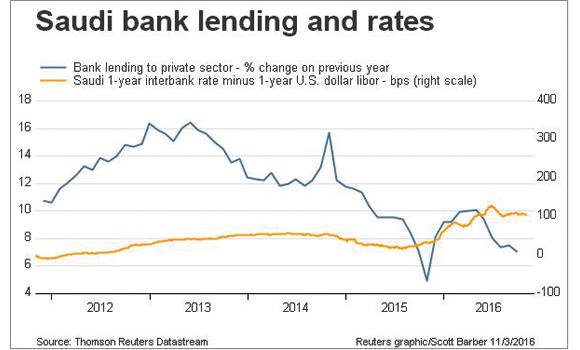

Bankers in contact with Saudi economic officials expect the 2016 budget deficit, which will be revealed when the government announces its 2017 budget plan in late December, to come in well below Riyadh’s original projection of SR326 billion.

Al-Sudairi predicted a deficit of SR190 billion; Jadwa Investment, a leading investment bank, forecasts SR265 billion. Such a figure would allow Riyadh to claim major progress in its effort to eliminate the deficit by 2020.

Some of the progress, though, is due not to sustainable spending cuts but to unpaid bills.

The government has reduced or suspended payments that it owes to construction firms, medical establishments and even some of the foreign consultants who helped to design the economic reforms. Al-Sudairi estimated unpaid dues for construction firms alone totaled SR80 billion.

This reduces Riyadh’s outgoings for now but stores up obligations in the future. It also worsens the impact on the economy of state spending cuts and has contributed to severe financial problems at some big construction firms.

Outgoing

Finance Minister Ibrahim Al-Assaf said in mid-October that payments to construction firms would now rise — apparently a recognition of the damage that the payment delays were doing to the economy.

Finance Minister Ibrahim Al-Assaf said in mid-October that payments to construction firms would now rise — apparently a recognition of the damage that the payment delays were doing to the economy.

Signs of the economic slump can be seen in Riyadh and other major cities, where discounts of 50 percent or more are offered by stores selling clothes and consumer electronics, and there is a surge in people offering second-hand cars for sale.

There used to be long waiting lists for compounds housing well-off expatriates; the lists have shrunk or disappeared, and more villas in the compounds are vacant.

The non-oil sector of the economy has shrunk from a year earlier in two of the three-quarters through June, while earnings of listed Saudi companies shrank 2 percent in the third quarter of 2016, NCB Capital calculated.

There may be worse to come. In September, the government cut allowances paid to employees the public sector, where two-thirds of Saudis work; some analysts estimated this might reduce those people’s disposable incomes by 20 percent. Saudi Arabian Monetary Agency has spread some of that pain to the banking sector by telling banks to reschedule public employees’ consumer and property loans.

“The public sector pay cuts were a shock. The effect will spread through the economy in the next few months,” said a senior fund manager in Riyadh.

“For the corporate sector, the first quarter of next year will be the worst.”

The economy is expected to start recovering in the second half of 2017, he said.

But several factors suggest the recovery may be slow and uncertain.

Between 1 million and 2 million of Saudi Arabia’s 10 million foreign workers may leave over the next couple of years as the economic slowdown causes lay-offs and the government seeks to steer Saudi citizens into jobs previously held by foreigners, said a top executive at a big Saudi company.

That would reduce outward remittances of money, helping Saudi Arabia’s balance of payments further, but it would drag on economic growth.

The official unemployment rate among citizens is likely to rise to 13 percent next year from 11.6 percent, a local economist said.

The planned introduction of a 5 percent value-added tax in 2018, an important step to strengthen state finances, will also hit consumption.

The biggest uncertainty may be how authorities can push through a key part of their reform drive — fostering a vibrant private sector that does not depend on oil revenues — in the face of austerity policies that are suppressing private demand.

For example, the government is trying to stimulate the housing industry.

But Jamil Ghaznawi, local director of real estate services firm JLL, said smaller developers — who provided 85 percent of the stock in the market — had actually slowed their activity in the past 18 months as austerity reduced homebuyers’ incomes and weakened construction firms’ finances.

No Comments For This Post, Be first to write a Comment.

Most viewed from International

Most viewed from World

AIMIM News

Latest Urdu News

Most Viewed

May 26, 2020

Do you think Canada-India relations will improve under New PM Mark Carney?

Latest Videos View All

Like Us

Home

About Us

Advertise With Us

All Polls

Epaper Archives

Privacy Policy

Contact Us

Download Etemaad App

© 2025 Etemaad Daily News, All Rights Reserved.

.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)