Breaking news: You can’t believe what President Trump says

Mon 23 Jan 2017, 23:18:47

I’ve spent the last few days reading accounts of President Trump’s inauguration speech, but I’m having a fundamental problem absorbing the analysis because I simply don’t believe anything he says.

I’m not just saying that I don’t believe that “carnage” describes the American condition (if it does, we need a new word for Syria), and I say that as someone who’s been trying for decades to get policymakers to pay attention to the economic costs of globalization.

I’m saying I don’t believe that he believes it.

From his speeches to his tweets, Trump does not speak truth. Instead, he speaks in two modes. One, he says what his audience wants to hear, and two, he does his “Art of the Deal” shtick, trying to put perceived enemies and negotiating opponents back on their heels.

Mode one is particularly easy to see; it’s what he does in front of crowds. He tells coal workers he’ll bring their jobs back. He tells those unhappy with their health insurance that his plan will provide more coverage for less money. He reassures the New York Times editorial board that he’s a moderate on climate change (“I’m looking at it very closely”).

He can’t bring back coal jobs; he’s got no plan for better health insurance, in no small part because it’s impossible to provide more comprehensive coverage while spending less. Days after his meeting with the Times, he nominated Scott Pruitt, an avowed enemy of climate policy, to head the Environmental Protection Agency.

His inaugural speech was full of populist rhetoric about helping those who’ve been on the wrong side of globalization and inequality. He boldly asserted that “every decision on trade, on taxes, on immigration, on foreign affairs, will be made to benefit American workers and American families.”

How likely is that? It’s early days, of course, and actions yet to come will speak louder than these words. But look at his Cabinet, look at his tax plan and the budgets of his Republican congressional majority. Observe that on the day he spoke those words, he signed an executive order to effectively gut Obamacare’s individual mandate with no replacement in sight, raised the cost of mortgages to low and moderate-income home buyers, and expunged reports on climate change and gay rights from the government’s website.

Mode two is obvious in tweet-shaming China, threatening to punish companies that offshore jobs, 45 percent tariffs, the wall that he still claims Mexico will pay for, and most recently, falsely accusing the press of dishonestly reporting the size of the crowd at his inauguration. The idea here is that when actual negotiations on these matters commence, his opponents, which clearly include the media, will already be playing defense. That may or may not be an effective strategy — my guess is that it gets old pretty quickly — but that’s what’s going on.

I don’t believe a word he says, and neither should you.

What does that mean from the perspective of both the media

and the analytic community? Regarding the latter, I’m thinking about my own economic policy lens, but also that of the many foreign policy actors who are trying to figure out how to deal with our new president. (I’ve had numerous conversations with embassy officials here in the District who’ve asked me some version of this question.)

and the analytic community? Regarding the latter, I’m thinking about my own economic policy lens, but also that of the many foreign policy actors who are trying to figure out how to deal with our new president. (I’ve had numerous conversations with embassy officials here in the District who’ve asked me some version of this question.)

Starting with the media, I asked a reporter I much admire whether her paper really had to report Trump’s tweets, given that whatever information they contain is wholly unreliable. Her reply was, “Of course! They’re news.” Her paper’s solution is to provide context within which to place the tweet, which I took to mean some version of “the president may or may not mean what he says here.”

That means that all of us — voters, journalists, foreign officials, policy analysts — must either quickly learn this lesson, i.e., he doesn’t mean what he says, or suffer severe mental whiplash on a daily basis while missing what’s really going on.

But how can we possibly figure out what he’s really up to?

For one, as alluded to above, you look at who he’s surrounding himself with, which, contrary to his populist campaign, are Wall Street bankers, education privatizers (Betsy DeVos), anti-safety-net advocates (Ben Carson), and business-oriented globalizers (Rex Tillerson). It’s unclear whether he’ll listen to them — for the most part, their unifying theme is that they’re really rich and were loyal to him during the campaign — but I have an easier time seeing this crew cutting taxes on the wealthy and regulations on business/finance than lifting the living standards of the working class. (And note that, thus far, their announced agenda is all the former and none of the latter.)

Look at the budgets and tax plans that the Republican majority has had on the shelf for years now. The budgets cut deeply in low-income programs; the tax cuts enrich the wealthy while starving the Treasury of much-needed revenue. This is not speculation; these documents exist, and we’ve analyzed them.

What is more speculative, though still based on stated preferences and some policy work of powerful Republicans, is the desire to pay for these tax cuts by cutting Social Security and Medicare. Trump says he won’t go there, but what did I just tell you what Trump says?

Throughout history, demagogues have used populism to “dangle the keys,” to get people to “look over here” while “over there,” they engage in activities that are diametrically opposed to the public good. This was clear in his inaugural speech, as Trump blamed government for everything that’s gone wrong while ignoring the finance and corporate sectors that brought us the financial bubble and offshoring of jobs.

Our job is thus not to be distracted by shiny objects, to keep our eye on the power, the budget, the social insurance, the facts, the numbers, the vulnerable, the safety net and the public good. I will not go gently into the fact-free night, and I expect you won’t either.

No Comments For This Post, Be first to write a Comment.

Most viewed from International

Most viewed from World

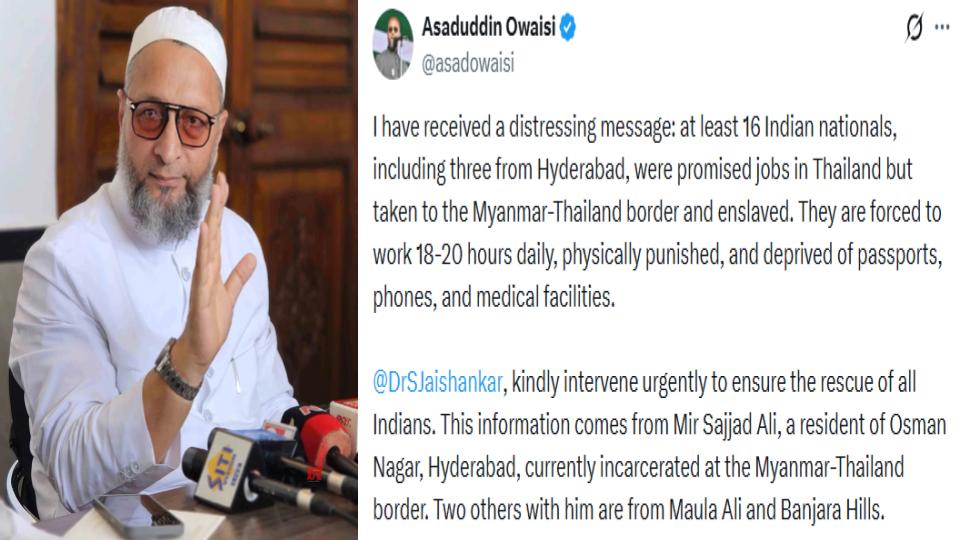

AIMIM News

Latest Urdu News

Most Viewed

May 26, 2020

Should there be an India-Pakistan cricket match or not?

Latest Videos View All

Like Us

Home

About Us

Advertise With Us

All Polls

Epaper Archives

Privacy Policy

Contact Us

Download Etemaad App

© 2026 Etemaad Daily News, All Rights Reserved.

.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)