Erdogan 'needs every vote' and is looking to Turks in U.S. for support

Thu 19 Apr 2018, 19:21:14

ISTANBUL — A year after his bodyguards brawled with protesters on a Washington street, Turkey's strongman president is bringing his ruling party to the United States in what observers say is a campaign to improve its battered reputation.

President Recep Tayyip Erdogan's Justice and Development Party, or AKP, has announced plans to open offices in the U.S. and six other countries as he seeks to rally support among the Turkish diaspora.

The last time Erdogan was tested at the ballot box, he secured sweeping new powers in a constitutional referendum last year with just a 51 percent “yes” vote. That means the country will switch from a parliamentary system to a presidential system that abolishes the office of the prime minister and decreases the powers of the parliament.

Erdogan announced Wednesday that snap elections would be held June 24 — more than a year before they were due to occur. The vote hadn't been expected until November 2019.

"The diseases of the old system confront us at every step we take," he said in a speech broadcast live on television.

Some analysts believe the close referendum result suggests even a relative small number of votes could decide Erdogan’s future as an ailing economy and increasing divisions within the country's nationalist movement potentially threaten his grip on power.

Some analysts believe the close referendum result suggests even a relative small number of votes could decide Erdogan’s future as an ailing economy and increasing divisions within the country's nationalist movement potentially threaten his grip on power.

In 2015, there were about 90,000 eligible Turkish voters in the U.S., Turkey's Hurriyet Daily News reported, and about 1.4 million in Germany.

Harun Armagan, the deputy chairman of AKP’s human rights committee, told NBC News that the overseas outreach was aimed at spelling out "what we’ve done and what we will be doing."

However, party officials were tight-lipped about which cities the offices would be located in and when they would open.

However, party officials were tight-lipped about which cities the offices would be located in and when they would open.

Previous attempts to influence Turkish citizens now living abroad led to controversy in other Western countries.

In the lead up to last year's referendum vote, Germany and the Netherlands banned some rallies and visits from Turkish officials, citing security concerns. Erdogan called the moves “Nazi-like.”

Aykan Erdemir, a senior fellow at the Washington-based Foundation for Defense of Democracies and a former lawmaker with Turkey’s CHP opposition party, said the new offices would provide Erdogan with "an opportunity to reach out directly" to Turkish citizens living abroad.

"Every vote counts, it might be a close second round in the presidential election," he added.

Aykan Erdemir, a senior fellow at the Washington-based Foundation for Defense of Democracies and a former lawmaker with Turkey’s CHP opposition party, said the new offices would provide Erdogan with "an opportunity to reach out directly" to Turkish citizens living abroad.

"Every vote counts, it might be a close second round in the presidential election," he added.

Erdemir said that simmering tensions between Washington and Ankara likely also played a role in the decision to set up an office in the U.S.

"The AKP has been suffering from an image problem in the U.S,” he said. “Probably the primary aim is to

reach the U.S. government and U.S. policymakers."

reach the U.S. government and U.S. policymakers."

Turkey’s reputation suffered a major blow on U.S. soil when security officials fought protesters in Washington during Erdogan's visit to see President Donald Trump last May. A dozen members of Erdogan's security detail — nine security officers and three police officers — were charged with taking part in the melee while the Turkish leader looked on.

U.S. prosecutors recently dismissed criminal charges against 11 of Erdogan's bodyguards stemming from the Washington brawl.

U.S. prosecutors recently dismissed criminal charges against 11 of Erdogan's bodyguards stemming from the Washington brawl.

In September, a protester was punched by Turkish security while being physically forced from the room during a speech by Erdogan at a New York hotel.

Tensions between the two NATO allies have increased further because of differences over military operations in Syria, where Turkish troops recently launched a military offensive against the U.S.-backed Kurdish militia, the YPG.

Tensions between the two NATO allies have increased further because of differences over military operations in Syria, where Turkish troops recently launched a military offensive against the U.S.-backed Kurdish militia, the YPG.

Ankara says the YPG is linked to the Kurdish Worker’s Party, a militant group in Turkey that both Ankara and Washington recognize as a terrorist organization.

U.S. support for Kurdish fighters, which Turkey views as a threat to its national security, had already helped sour relations between the two countries.

Erdogan's international standing has also been weakened by a purge of opponents that followed a failed 2016 coup.

Erdogan's international standing has also been weakened by a purge of opponents that followed a failed 2016 coup.

The Turkish leader blames cleric Fethullah Gulen, who lives in self-imposed exile in Pennsylania, for masterminding the bid to topple him. Gulen denies that allegation.

Erdogan demanded the extradition of Gulen but Washington said it did not receive evidence of his involvement in the putsch.

Investigators with special counsel Robert Mueller's probe were looking into whether former National Security Adviser Michael Flynn met with senior Turkish officials just weeks before Trump's inauguration about a potential quid pro quo in which Flynn would help orchestrate Gulen's return to Turkey. Flynn is now cooperating with the inquiry.

AKP already has offices in Brussels, Belgium, and in the Turkish-Cypriot state in northern Cyprus that is only recognized by Turkey.

Investigators with special counsel Robert Mueller's probe were looking into whether former National Security Adviser Michael Flynn met with senior Turkish officials just weeks before Trump's inauguration about a potential quid pro quo in which Flynn would help orchestrate Gulen's return to Turkey. Flynn is now cooperating with the inquiry.

AKP already has offices in Brussels, Belgium, and in the Turkish-Cypriot state in northern Cyprus that is only recognized by Turkey.

In addition to the U.S., new offices are planned for Germany, the U.K., France, Russia, Macedonia, and Bosnia-Herzegovina.

Armagan, the AKP official, added that Erdogan's party would also seek permission to hold rallies in Europe and the U.S. He said the party was eager to counter what it perceives as unfair media coverage and the influence of Gulen.

In the Netherlands, violent clashes broke out when Turkish ministers tried to attend pro-Erdogan rallies during last year's constitutional referendum. When Dutch authorities outlawed the visits, Erdogan called them “Nazi remnants” and “fascists."

In the Netherlands, violent clashes broke out when Turkish ministers tried to attend pro-Erdogan rallies during last year's constitutional referendum. When Dutch authorities outlawed the visits, Erdogan called them “Nazi remnants” and “fascists."

No Comments For This Post, Be first to write a Comment.

Most viewed from International

Most viewed from World

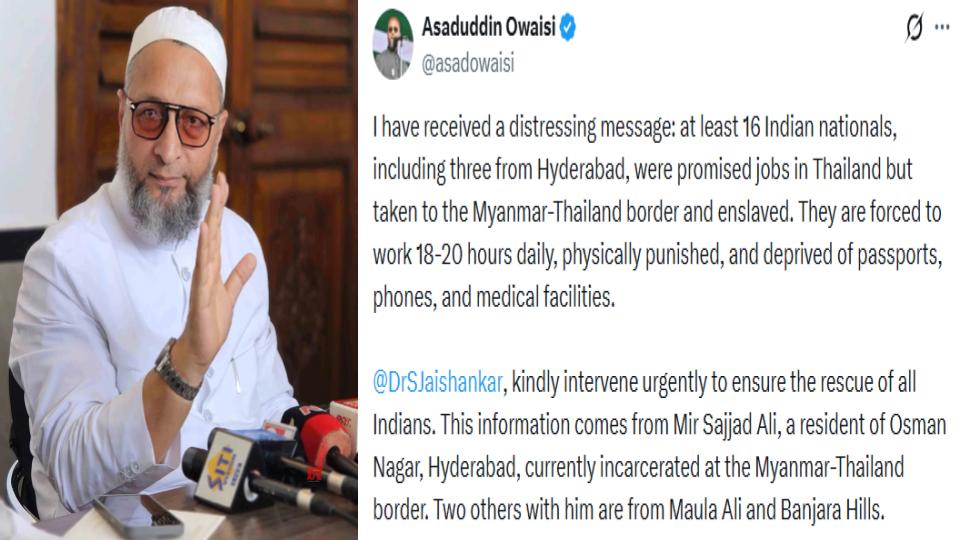

AIMIM News

Latest Urdu News

Most Viewed

May 26, 2020

Is it right to exclude Bangladesh from the T20 World Cup?

Latest Videos View All

Like Us

Home

About Us

Advertise With Us

All Polls

Epaper Archives

Privacy Policy

Contact Us

Download Etemaad App

© 2026 Etemaad Daily News, All Rights Reserved.

.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)