Gen Sharif’s moves to Riyadh

Tue 10 Jan 2017, 11:22:51

There is more than one way to interpret the recent news that retired General Raheel Sharif has relocated to Riyadh to take charge of the so-called alliance of Islamic countries built by Saudi Arabia, ostensibly to fight Daesh.

The refreshingly widespread reaction in Pakistan seems to have been one of contempt and confusion. Why would a man that so many Pakistanis had adopted as this country’s favourite son don the agenda of a foreign power, so soon after leaving office as the chief of army staff? Especially when the foreign power in question is the House of Saud, which is experiencing a transition unlike any other in its history.

The question of whether Pakistani soldiers, even retired ones, should be in the business of working for foreign governments is an interesting one. But it cuts several ways. Lots of foreign governments engage with the Pakistani armed forces in a whole range of integral transactions, from providing technical know-how and support to sharing the hardware necessary for Pakistan to remain secure. From China to the US to the UK to Turkey, foreign governments engage with Pakistani soldiers, both serving and retired, in all kinds of legitimate and mutually beneficial relationships.

What we need to do is employ some common sense in discerning between good kinds of working with foreign governments and bad kinds of working with foreign governments. It, therefore, seems fair that we try to examine Gen Sharif’s choice more carefully, to determine which kind it actually is.

Should we object to his decision based on distaste for Pakistani troops operating outside any theatre beyond the scope of our national boundaries? There are plenty of puritans who would make this argument. However, they would need to contend with at least two counter-arguments. The first is our history of enthusiastic deployment of Pakistani troops as UN peacekeepers the world over. The second is the necessary deployment of serving officers around the world for intelligence gathering and espionage. Of course, both these counter-arguments are bunkum. Pakistani peacekeepers and intel operatives work strictly within the scope of the national interest (contested as that may be, here at home). The relevant question then is whether having Gen Raheel Sharif working for the Saudi-led alliance is strictly, or even broadly, within the scope of Pakistan’s national interest.

This is a complex question. The first thing we need to accept is the sectarian-coding already infused in the question. We have allowed the Shia-Sunni divide to grow like a cancer in our essentially once-upon-a-time non-sectarian society for so long that it is a fiction for us to pretend that any discussion in the public domain of Saudi Arabia and/or Iran can be spared the sectarian leanings of our society. So let’s try to answer the question whilst consciously avoiding a sectarian leaning: Can a Pakistani general working for the Saudis ever be in the Pakistani national interest?

The obvious, objective answer to this question is: of course it can. But it depends – on the context, the timing, and the mission he or she is assigned once in Riyadh.

Saudi Arabia is a complicated country that has to contend with an unprecedented range of challenges. There are existential threats to the established order of power in Saudi Arabia, and these threats combine with serious economic threats to Saudi Arabia’s wealth. But it wasn’t always 2017. For decades, Saudi Arabia’s wealth and power was incomparable to any other country’s. In those days, Pakistan was a frequent bidder for Saudi financial and political support. And to be fair, those days aren’t really that far back in the rear view mirror. The most recent infusion of Saudi cash into Pakistani coffers was as recently as March 2014, when Finance Minister Ishaq Dar demanded that cantankerous reporters, columnists and television anchors stop making the gift of a

“friendly country” controversial.

The benevolent edifice of this relationship was established in advance of the era of petro-excess in the 1980s, thanks to the ‘Islamic socialism’ construct of Pakistani foreign policy, under Prime Minister Zulfikar Ali Bhutto in the 1970s. We can argue till the cows come home as to whether these facts could have been altered, but we cannot argue the facts themselves. There is at least some moral obligation for Pakistan to consider Saudi needs in its calculus about how to respond to requests for our help.

Luckily, we don’t need to depend on reporters, columnists and television anchors to ascertain real wisdom. Parliament had a chance to discuss and debate these realities; and it made a very clear choice in April 2015: to eschew an active role in supporting the Saudi Arabian intervention in Yemen. This wisdom is the qualified will of the people of Pakistan – and, therefore, relatively non-negotiable.

Yet, it would be premature to end the conversation here. Saudi Arabia is not only a net contributor to Pakistani solvency, but also a host to over a million Pakistani workers whose remittances are a valuable source of remittances. There is a decent response to this too. The Gulf countries owe their incredible infrastructure and comforts, at least in part, to the very labour that is cited in discussions like this. Pakistan may need remittances of foreign workers, but Gulf countries need those workers as much, if not more. Attempts to alter the demographics of labour imports in the Gulf are not new, and Pakistanis needn’t be shy about it: we are as integral to the day-to-day operations of the Gulf as any nation’s people.

This leaves the big elephant in the room. One very compelling reason to go along with Gen Sharif’s decision to lead the Saudi anti-Daesh alliance is to assuage concerns that Pakistan is leaning too far toward Tehran in recent months. The evidence for these concerns, however, is incredibly thin. This is the inherent risk in any course correction. Pakistan’s unquestioning loyalty to Saudi Arabia’s worldview has lasted for so long that any course correction is going to be seen as nod to Iran.

The first problem with this is that it problematises a pro-Iran stance in Islamabad. Pakistan should be running miles away from any such stance of course. Iran is an aggressive regional power, and it has played a significant role in the deepening of the sectarian crisis across the Muslim world. However, the choice of leaning Iran-ward or not should be Pakistan’s to make, of its own volition. It should not have to be informed by Riyadh’s opinion on the matter. The second problem is that it establishes the precedent of softening the blow of decisions made by the parliament of Pakistan with the deployment of retired army officers. One can hardly imagine a better way of sharpening the edges of our already robust civil military disequilibrium.

Pakistanis and Saudis are joined in a fraternity that is much deeper than ordinary Western analyses can capture. Millions of ordinary Pakistanis have a deep and irrevocable bond with the Saudi people. These bonds cannot be conditioned on sect or on how Pakistan pursues its national interest. Looking at the cancerous sectarian violence across various parts of the Muslim world, it is clear that nothing can be more central to Pakistan’s national interest than our traditional sectarian harmony, rooted in our unique brand of Islam: captured by our Sufi saints, from Bulleh Shah to Baba Farid to Nizamuddin to Baba Rehman.

Neither our love for our Saudi brothers, nor our frustration with our Persian brothers should ever let us forget our unique place in the Muslim world. Once upon a time, Pakistan was a pre-sectarian society. Its prosperous and secure future lies in becoming a post-sectarian society. Ultimately, that is the real measure to judge Gen Sharif’s decision to move to Riyadh.

The refreshingly widespread reaction in Pakistan seems to have been one of contempt and confusion. Why would a man that so many Pakistanis had adopted as this country’s favourite son don the agenda of a foreign power, so soon after leaving office as the chief of army staff? Especially when the foreign power in question is the House of Saud, which is experiencing a transition unlike any other in its history.

The question of whether Pakistani soldiers, even retired ones, should be in the business of working for foreign governments is an interesting one. But it cuts several ways. Lots of foreign governments engage with the Pakistani armed forces in a whole range of integral transactions, from providing technical know-how and support to sharing the hardware necessary for Pakistan to remain secure. From China to the US to the UK to Turkey, foreign governments engage with Pakistani soldiers, both serving and retired, in all kinds of legitimate and mutually beneficial relationships.

What we need to do is employ some common sense in discerning between good kinds of working with foreign governments and bad kinds of working with foreign governments. It, therefore, seems fair that we try to examine Gen Sharif’s choice more carefully, to determine which kind it actually is.

Should we object to his decision based on distaste for Pakistani troops operating outside any theatre beyond the scope of our national boundaries? There are plenty of puritans who would make this argument. However, they would need to contend with at least two counter-arguments. The first is our history of enthusiastic deployment of Pakistani troops as UN peacekeepers the world over. The second is the necessary deployment of serving officers around the world for intelligence gathering and espionage. Of course, both these counter-arguments are bunkum. Pakistani peacekeepers and intel operatives work strictly within the scope of the national interest (contested as that may be, here at home). The relevant question then is whether having Gen Raheel Sharif working for the Saudi-led alliance is strictly, or even broadly, within the scope of Pakistan’s national interest.

This is a complex question. The first thing we need to accept is the sectarian-coding already infused in the question. We have allowed the Shia-Sunni divide to grow like a cancer in our essentially once-upon-a-time non-sectarian society for so long that it is a fiction for us to pretend that any discussion in the public domain of Saudi Arabia and/or Iran can be spared the sectarian leanings of our society. So let’s try to answer the question whilst consciously avoiding a sectarian leaning: Can a Pakistani general working for the Saudis ever be in the Pakistani national interest?

The obvious, objective answer to this question is: of course it can. But it depends – on the context, the timing, and the mission he or she is assigned once in Riyadh.

Saudi Arabia is a complicated country that has to contend with an unprecedented range of challenges. There are existential threats to the established order of power in Saudi Arabia, and these threats combine with serious economic threats to Saudi Arabia’s wealth. But it wasn’t always 2017. For decades, Saudi Arabia’s wealth and power was incomparable to any other country’s. In those days, Pakistan was a frequent bidder for Saudi financial and political support. And to be fair, those days aren’t really that far back in the rear view mirror. The most recent infusion of Saudi cash into Pakistani coffers was as recently as March 2014, when Finance Minister Ishaq Dar demanded that cantankerous reporters, columnists and television anchors stop making the gift of a

“friendly country” controversial.

The benevolent edifice of this relationship was established in advance of the era of petro-excess in the 1980s, thanks to the ‘Islamic socialism’ construct of Pakistani foreign policy, under Prime Minister Zulfikar Ali Bhutto in the 1970s. We can argue till the cows come home as to whether these facts could have been altered, but we cannot argue the facts themselves. There is at least some moral obligation for Pakistan to consider Saudi needs in its calculus about how to respond to requests for our help.

Luckily, we don’t need to depend on reporters, columnists and television anchors to ascertain real wisdom. Parliament had a chance to discuss and debate these realities; and it made a very clear choice in April 2015: to eschew an active role in supporting the Saudi Arabian intervention in Yemen. This wisdom is the qualified will of the people of Pakistan – and, therefore, relatively non-negotiable.

Yet, it would be premature to end the conversation here. Saudi Arabia is not only a net contributor to Pakistani solvency, but also a host to over a million Pakistani workers whose remittances are a valuable source of remittances. There is a decent response to this too. The Gulf countries owe their incredible infrastructure and comforts, at least in part, to the very labour that is cited in discussions like this. Pakistan may need remittances of foreign workers, but Gulf countries need those workers as much, if not more. Attempts to alter the demographics of labour imports in the Gulf are not new, and Pakistanis needn’t be shy about it: we are as integral to the day-to-day operations of the Gulf as any nation’s people.

This leaves the big elephant in the room. One very compelling reason to go along with Gen Sharif’s decision to lead the Saudi anti-Daesh alliance is to assuage concerns that Pakistan is leaning too far toward Tehran in recent months. The evidence for these concerns, however, is incredibly thin. This is the inherent risk in any course correction. Pakistan’s unquestioning loyalty to Saudi Arabia’s worldview has lasted for so long that any course correction is going to be seen as nod to Iran.

The first problem with this is that it problematises a pro-Iran stance in Islamabad. Pakistan should be running miles away from any such stance of course. Iran is an aggressive regional power, and it has played a significant role in the deepening of the sectarian crisis across the Muslim world. However, the choice of leaning Iran-ward or not should be Pakistan’s to make, of its own volition. It should not have to be informed by Riyadh’s opinion on the matter. The second problem is that it establishes the precedent of softening the blow of decisions made by the parliament of Pakistan with the deployment of retired army officers. One can hardly imagine a better way of sharpening the edges of our already robust civil military disequilibrium.

Pakistanis and Saudis are joined in a fraternity that is much deeper than ordinary Western analyses can capture. Millions of ordinary Pakistanis have a deep and irrevocable bond with the Saudi people. These bonds cannot be conditioned on sect or on how Pakistan pursues its national interest. Looking at the cancerous sectarian violence across various parts of the Muslim world, it is clear that nothing can be more central to Pakistan’s national interest than our traditional sectarian harmony, rooted in our unique brand of Islam: captured by our Sufi saints, from Bulleh Shah to Baba Farid to Nizamuddin to Baba Rehman.

Neither our love for our Saudi brothers, nor our frustration with our Persian brothers should ever let us forget our unique place in the Muslim world. Once upon a time, Pakistan was a pre-sectarian society. Its prosperous and secure future lies in becoming a post-sectarian society. Ultimately, that is the real measure to judge Gen Sharif’s decision to move to Riyadh.

No Comments For This Post, Be first to write a Comment.

Most viewed from International

Most viewed from World

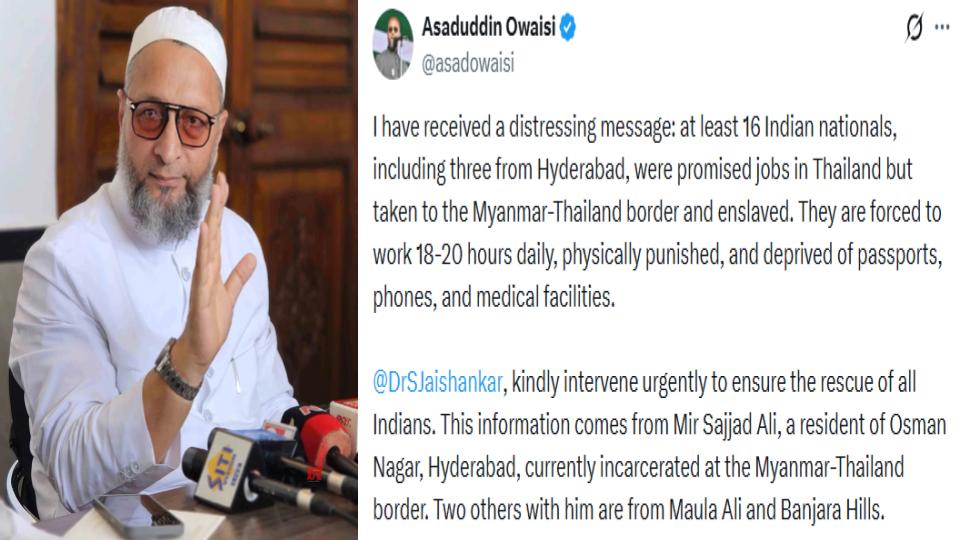

AIMIM News

Latest Urdu News

Most Viewed

May 26, 2020

Which cricket team is your favourite to win the T20 World Cup 2026?

Latest Videos View All

Like Us

Home

About Us

Advertise With Us

All Polls

Epaper Archives

Privacy Policy

Contact Us

Download Etemaad App

© 2026 Etemaad Daily News, All Rights Reserved.

.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)