Has Duterte really ditched the US for Beijing's embrace?

Fri 21 Oct 2016, 15:23:50

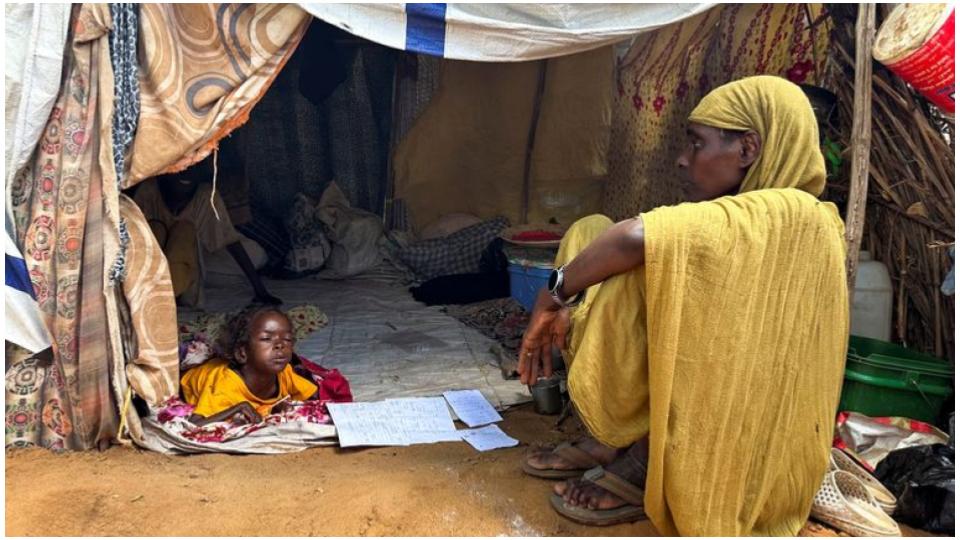

The Philippines’ president, Rodrigo Duterte, jetted into Beijing this week telling journalists “only China can help us” – and help it did.

The 71-year-old populist was set to return from his four-day state visit on Friday having secured a reported $13.5bn (£11bn) in deals and a lucrative new alliance with the Asian giant.

“It has the potential to be [a turning point in Philippine history],” one Manila broadsheet said of Duterte’s “pivot to China” after he delighted an audience of Communist party grandees in the Great Hall of the People by declaring his “separation” from the United States and new allegiance to Beijing.

On the surface, Duterte’s visit represents a resounding diplomatic success for both sides after years of toxic relations thanks to the tussle over disputed territories in the South China Sea.

For the Chinese leader, Xi Jinping, who is about to complete four years in power, it was a rare foreign policy triumph following a series of setbacks including South Korea’s decision to deploy the US Thaad missile defence system and a humiliating rebuke from an international tribunal over its claims in the South China Sea.

By seducing Washington’s best friend in south-east Asia, Xi, at a stroke, undermined one of the key planks of Barack Obama’s foreign policy – the “pivot to Asia” bid to counter Beijing’s influence in the region.

“This was a huge strategic coup for the Chinese,” said Richard Javad Heydarian, a Manila-based foreign affairs expert and author.

Shi Yinhong, an international relations professor and government adviser from China’s Renmin University, said Beijing believed improving previously frosty relations with Manila would boost its regional standing and, eventually, “weaken America’s strategic position in the western Pacific”.

Yet, in order to secure the collaboration of a key US ally, China had promised only limited economic assistance and select political favours that did not involve making a single concession over its territorial claims, Shi pointed out. “It’s a good deal for China.”

For Duterte, whose country has missed out on Beijing’s regional munificence as a result of the South China Sea feud, there was a prize too.

Reports in his country’s media suggested he and Xi sealed 13 agreements and memorandums of understanding during the visit, with China offering $6bn in soft government loans, $3bn in credit from Chinese banks and a 100m yuan (£12m) contribution to Manila’s war on drugs.

But as the Philippine leader flew home to trumpet his achievements, many questions remained. Would he really break off ties with the US, for years one of his country’s closest allies? If so, at what cost? And how might Washington react to Duterte’s public rejection of its friendship?

“He still could change his words in the future,” said Shi .

“Now he is in Beijing and he is speaking words to a Chinese audience,” he added. “But after Beijing he will be in Tokyo. I think what he will say in Tokyo will naturally be somewhat different from what he said in Beijing. Philippines-American relations have been damaged, of course. But still, this is only the beginning. In the future nothing is certain.”

In Washington officials share the view that the unpredictable Philippine leader could easily pivot back to the US if he believes it better serves his interests.

“There is no question that Duterte is … trying to play the well-worn game of playing us off against the Chinese,”.

Indeed, just hours after Duterte announced his breakup with America, his trade minister Ramon Lopez denied such a split

would occur.

would occur.

Indeed, just hours after Duterte announced his breakup with America, his trade minister Ramon Lopez denied such a split would occur.

“Let me clarify. The president did not talk about separation,” he told CNN Philippines, adding: “We definitely won’t stop the trade and investment activities with the west, specifically the US.”

While Duterte has vowed to end joint maritime patrols in the South China Sea and called for US special forces to leave the southern island of Mindanao, no concrete steps appear to have been taken to realise them.

Even so, the swiftness and venom with which Duterte has spurned his country’s most powerful ally – he has repeatedly called Barack Obama a “son of a whore” – has caused alarm in the Philippines, both on the streets and the corridors of power.

“What is unfolding before us must be considered a national tragedy,” the country’s former foreign minister, Albert del Rosario, said in a scathing statement released on Friday.

Del Rosario said Duterte’s rush to ditch the US in favour of “an aggressive neighbour that vehemently rejects international law” was both unwise and incomprehensible.

“Did the Chinese give [Duterte] too much Maotai?” one commentator wrote in the the Philippine Star, referring to the luxury Chinese liquor with which politicians have traditionally plied their guests.

“There are people in the Philippines who are already raising their eyebrows. I hear commentaries like, ‘Was it a state visit or was it a tributary visit by the Filipino sultan to the Ming dynasty?’” he said.

Joseph Franco, a Philippines specialist from Singapore’s Nanyang Technological University, said Duterte’s “wild and crazy statements” had also left many within the political and military establishment on edge .

“It’s like Kim Jong-un minus the nukes,” he said.

Franco, who used to work for the chief of staff of the Philippines armed forces, said officials were desperately trying to understand “where does the hyperbole and rhetoric end and where does the policy begin?”

“I know people who are at their wits end, frankly, within the the foreign ministry and the army.”

“The Philippine military is very close to America and relies on full-spectrum American support – logistics, intelligence, finance and training – so I don’t think the military will be happy with severance of ties with the US in favour of China,” he said.

The military is “influential in the sense that they can get rid of any president at some point in time,” Heydarian added. “The Philippines is a country where coup d’états have not been very uncommon.”

Shi Yinhong, the Chinese foreign policy scholar, said Duterte’s rapprochement with Beijing was likely to “stimulate further the pro-American forces in the Philippines to undermine his domestic position”.

He added that Chinese leaders would be weighing up how much faith they could place in a special relationship with someone he described as “generally a very, very volatile guy”.

Asked if Beijing trusted Duterte, the academic replied: “This is international politics. There is no baseline trust. How can anyone trust this guy?”

No Comments For This Post, Be first to write a Comment.

Most viewed from International

Most viewed from World

AIMIM News

Latest Urdu News

Most Viewed

May 26, 2020

Do you think Canada-India relations will improve under New PM Mark Carney?

Latest Videos View All

Like Us

Home

About Us

Advertise With Us

All Polls

Epaper Archives

Privacy Policy

Contact Us

Download Etemaad App

© 2025 Etemaad Daily News, All Rights Reserved.

.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)