'I Thought, This Is It': One Man's Escape From An Islamic State Massacre

Tue 15 Nov 2016, 18:55:54

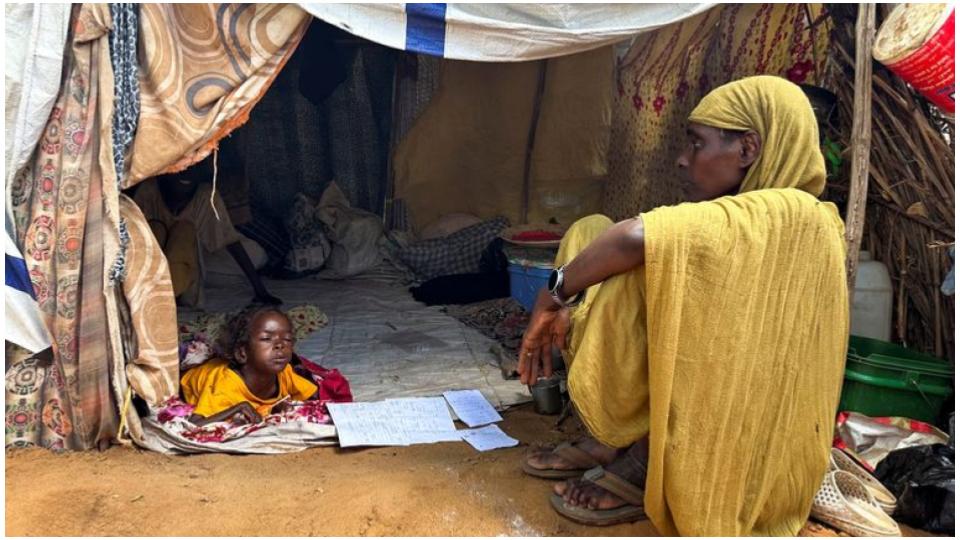

SAFIYA, IRAQ: Blindfolded and bound, his knees pressing into the dirt, Imad resigned himself to what seemed inevitable: He was going to die.

Islamic State gunmen had driven him and about 90 other former Iraqi police and army officers to a remote industrial area on the edge of Hamam al-Alil, 10 miles south of Mosul, after rounding them up from their villages last month.

Iraqi security forces were approaching, and the militants were losing their grip on the area.

Packed into two pickup trucks and a bus, the men were told they were being taken to see their families, but they were instead slated for execution.

Imad's truck was the first to be unloaded, and he was the first in line. A militant took him by the arm.

He walked around 10 yards.

He was ordered to kneel down.

"I thought, 'This is it, it's over,' " he said as he recounted his ordeal from his home in the village of Safiya. "We've lived under the rule of Islamic State for more than two years and we know that nobody survives such things."

The gunmen opened fire.

Imad's account of what happened that day provides a rare firsthand view of the brutality that has become a notorious hallmark of the Islamic State's rule.

The militants have steadily lost ground since Iraqi forces began their offensive to recapture Mosul a month ago, breaking into the city from the east and capturing towns and villages to the south.

Increasingly cornered, they have fought to hold their last remaining stronghold in Iraq any way they can. They have held civilians as human shields and dispatched hundreds of car bombs.

Inside the city and other areas on the outskirts under their control, they have also lashed out with mass arrests and executions.

Those who served in the police and army have borne the brunt of recent mass killings, whether they were accused of collaborating with the advancing forces, or simply attacked out of vengeance.

The United Nations reported last week that the Islamic State had abducted 295 former members of the Iraqi security forces from areas around Mosul. It also said that 50 former police officers had been executed in Hamam al-Alil last month. Imad said nearly double that number were killed at the place he was taken, which is near a cement factory northwest of the town.

Iraqi police forces said Monday that they had found a mass grave at that location containing around 100 bodies, corroborating Imad's account. Police spokesman Ammar al-Jazairi said they are thought to be the bodies of former police officers rounded up after the Mosul operation began.

That follows the discovery of another mass grave at a bombed-out agricultural college in the town after it was retaken by security forces this month. Iraqi security officials have also estimated that grave contains around 100 bodies.

In the days after Iraqi security forces began their offensive last month, the Islamic State had been rounding up entire villages farther south, forcing families to retreat to Mosul with them. Thousands arrived in Imad's village of Safiya, on their way north to Hamam al-Alil.

There were rumors that former police and army officers were being targeted for execution. When the Islamic State seized Mosul and surrounding towns and cities two and a half years ago, police and army officers were allowed to stay in their

territory if they repented through a process known as "towba."

territory if they repented through a process known as "towba."

But they were still viewed with suspicion, Imad said. That worsened as the militants' control began to crumble.

Imad had served on the police force for seven years.

He was at home with his wife and child when the militants announced over loudspeakers attached to vehicles that all men and boys 15 and older should gather at the mosque. "They said anyone who disobeyed would be killed," said Imad, who spoke on the condition that his last name not be published because his wife and child are still in Islamic State territory.

"The Islamic State was breathing its last breath so I decided to run," he said.

He took off but was caught by the militants about 100 yards from his home and taken to where the men were gathered.

Former police and army officers were separated from the rest, loaded into trucks and cars and driven north to Hamam al-Alil. Civilians, including Imad's wife and baby, were marched on foot.

Imad was held in a house with more than 200 others from his village and communities around it. Those who had left the security forces before the Islamic State took control in 2014 were released, as were those who had worked as security guards for infrastructure such as oil facilities.

Around 90 remained.

The militants filmed each one, forcing them to give their name and the position they once held in the security forces.

They were blindfolded and their hands were bound. A prisoner asked one of the captors a question. Imad didn't hear it, but he heard the response.

"You are going to hell," the militant replied. That's when Imad knew for sure the fate that awaited them.

They were loaded into trucks and driven for half an hour along a dirt road.

It was dark by the time they reached the spot near the cement factory.

"I thought of my wife and son and how I'd never see them again," he said.

When the gunmen opened fire, he felt a bullet hit his leg.

"I got shot, but I didn't know how many times," he said. "I felt things hitting my back."

He fell forward into the dirt and pretended to be dead. He heard a commotion as someone from one of the other trucks tried to escape. The gunmen were distracted.

"They were screaming and shouting," he said. "As soon as I heard that, I saw my chance."

His hands had been only loosely bound with rope. He pulled them apart, tore off his blindfold and ran. It was only then that he realized he had been only lightly injured, a bullet grazing his leg. His back had been hit by stones kicked up by the bullets.

"It was dark, maybe they weren't that focused," he said. "It seems they were just shooting randomly."

A steep bank prevented the militants from chasing him in their vehicles. He walked all night before reaching an area controlled by security forces.

Some 22 former officers from his village died that day.

"As for me, I've seen death, and I feel reborn," he said. He worries about life under Iraqi forces, who he said damaged property in the village as they retook it.

Still, nothing will compare to the brutality of life under the Islamic State, he said: "Those people are monsters, killers; they don't have any humanity."

No Comments For This Post, Be first to write a Comment.

Most viewed from International

Most viewed from World

AIMIM News

Latest Urdu News

Most Viewed

May 26, 2020

Do you think Canada-India relations will improve under New PM Mark Carney?

Latest Videos View All

Like Us

Home

About Us

Advertise With Us

All Polls

Epaper Archives

Privacy Policy

Contact Us

Download Etemaad App

© 2025 Etemaad Daily News, All Rights Reserved.

.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)