India is becoming the world's new virus epicenter

Mon 31 Aug 2020, 19:41:23

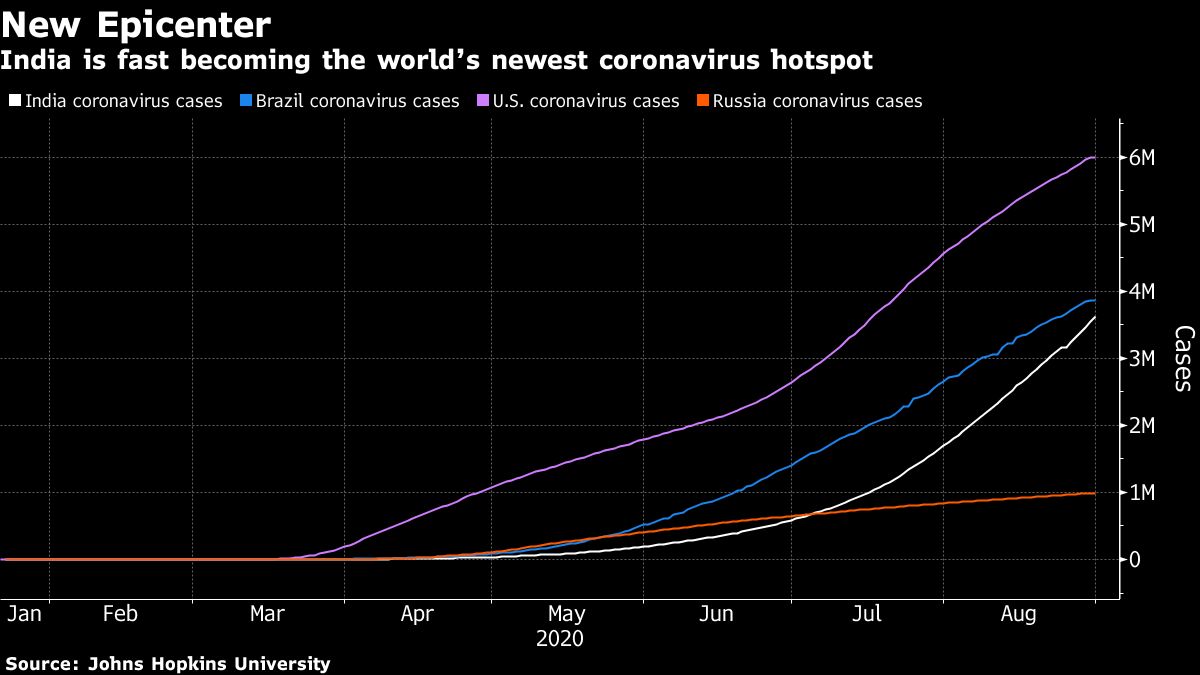

India is fast becoming the world’s new virus epicenter, setting a record for the biggest single-day rise in cases as experts predict that it’ll soon pass Brazil -- and ultimately the U.S. -- as the worst outbreak globally.

As many as 78,761 new cases were added Sunday, the most any country has ever reported in one day, while 971 deaths were reported on Monday, pushing the Asian country past Mexico for the third-highest number of deaths worldwide. At the current trajectory, India’s outbreak will eclipse Brazil’s in about a week, and the U.S. in about two months.

And unlike the U.S. and Brazil, India’s case growth is still accelerating seven months after the reporting of its first coronavirus case on Jan. 30. The pathogen has only just penetrated the vast rural hinterland where the bulk of its 1.3 billion population lives, after racing through its dense mega-cities.

As the world’s second largest country, and one with a relatively poor public health system, it’s inevitable that India’s outbreak becomes the world’s biggest, said Naman Shah, an adjunct faculty member at the country’s National Institute of Epidemiology.

“It would not be surprising, regardless of what India does,” said Shah, a member of the Indian government’s COVID-19 task force.

From the Philippines to Peru, the novel coronavirus poses a unique problem to poor countries: the densely packed slums where millions of their citizens live present ideal conditions for the virus to spread, while their economic precariousness means that the shutdowns necessary to contain the pathogen are intolerable.

Across the developing world, economies have been forced to open up even with the virus still running rampant, quickly overwhelming underfunded hospitals.

The list of worst-affected countries globally has accordingly shifted from rich to poor as the pandemic races around the world. Where once countries like Italy, Spain and the U.K. had the biggest outbreaks and highest death tolls, now the U.S is the only advanced economy in the top ten, among other developing nations like Mexico, Peru and South Africa.

Nowhere has the developing world’s plight played out more viscerally than in India, where an ambitious national lockdown imposed in March was lifted after two months as joblessness, starvation and a mass migration of workers leaving cities on foot became too much to

bear.

bear.

Prime Minister Narendra Modi’s government has since counseled the population to “live with the virus” while giving local officials freedom to impose restrictions on a state-by-state basis, which many have. The economy is projected to have contracted 18 per cent in the quarter to June from a year ago, more than any other major Asian country.

With antibody studies in capital New Delhi and other cities showing that the number of people with signs of past infection is between 40 and 200 times greater than the official case count, the true size of India’s epidemic is probably far larger than its reported 3.6 million infections.

And there is every reason to believe that the coronavirus is still only getting started in India. Much of the country’s coronavirus burden so far has fallen on its globally connected megacities like New Delhi and Mumbai, but the disease is now starting to shift to its rural hinterland where nearly 900 million people live, and health-care infrastructure is sparse. A lack of testing and medical help will likely mean that scores of infections and deaths are going unreported.

“The disease is moving from urban to rural areas, it’s moving from states with better health-care infrastructure to other places,” said Ramanan Laxminarayan, director of the New Delhi and Washington, D.C.-based Centre for Disease Dynamics Economics and Policy. “That all means that there will be more death, but they will not be counted because they will not be visible anywhere.”

The Modi government has often pointed to India’s official mortality rate of around 1.8 per cent -- among the lowest in the world -- as evidence that it is managing the virus’ spread, even if not containing it.

But deaths are likely substantially under-reported, and skewed by the country’s disproportionately young population -- 65 per cent are below the age of 35, the segment least in danger of dying from COVID-19. An age-adjusted analysis of India’s death rate by three economists at the National Bureau of Economic Research in Massachusetts found that India’s death rate was similar to the global average.

“What we’ve done is delayed infections, but we haven’t been able to curtail the transmission,” said CDDEP’s Laxminarayan. “And that was never going to be possible in a country the size of India and with the health infrastructure India has. What has played out is almost exactly what one should have expected.”

No Comments For This Post, Be first to write a Comment.

Most viewed from International

Most viewed from World

AIMIM News

Latest Urdu News

Most Viewed

May 26, 2020

Do you think Canada-India relations will improve under New PM Mark Carney?

Latest Videos View All

Like Us

Home

About Us

Advertise With Us

All Polls

Epaper Archives

Privacy Policy

Contact Us

Download Etemaad App

© 2025 Etemaad Daily News, All Rights Reserved.

.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)