Revealed: Why expats risk fines to live in shared accommodation

Mon 14 Nov 2016, 19:25:54

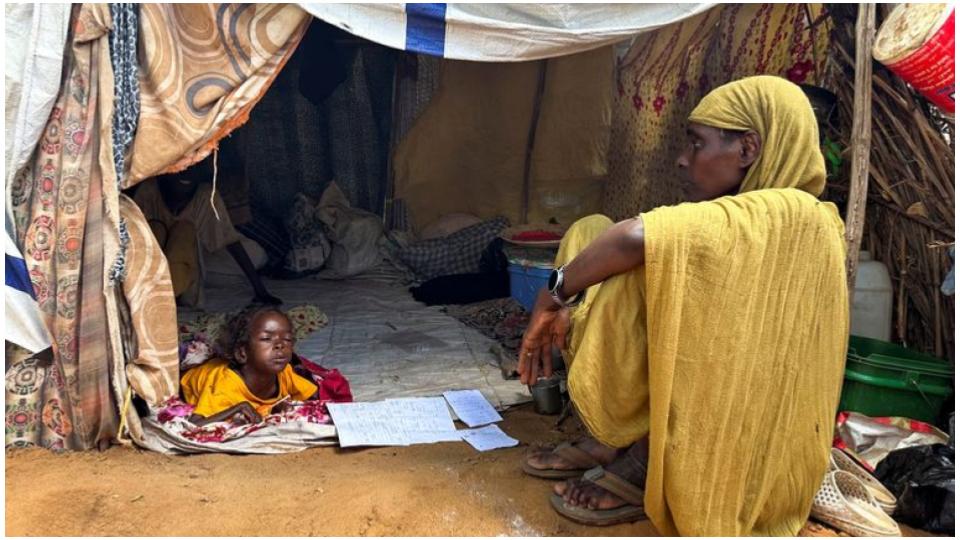

Dubai: For Marites, along with 23 other women who share a two-bedroom apartment in Al Barsha, the prospect of encountering municipality inspectors referred to as ‘baladiya’ — is just a part of daily life.

The Filipina teaching assistant employd at a school, who is in her fifties, has little choice but to share home space. She pays Dh800 monthly rent — utilities included — for a space on a bunk bed. To avoid the daily clamber up and down the bunk’s cold metal frame, she pays Dh50 extra for the lower berth.

“My salary is not too high. I have to send money to my family also,” says Marites.

At her school, full-time teachers get free housing provided by the school, a privilege not enjoyed by assistants.

However, though they live in sharing accommodation, Marites and her like do not really enjoy the prospect of sharing a bathroom, washing machine and kitchen with two dozen other people.

Arguments with flatmates take place often.

“Every individual has their own way of life. Sometimes there’s a conflict, but we can handle it,” she says. “You have no choice.’

To make it easier, Marites moved into an apartment occupied only by Filipinas. Living with other nationalities, with different cultural norms and cooking styles, proved to be far less comfortable.

Having a room all to herself is possible, but not practical. Per square foot, single rooms cost far more than entire apartments in the city’s outskirts.

“If you want one room, you have to spend a lot of money, but then you have no salary [left],” she adds.

Marites is just one of hundreds of thousands of Dubai’s residents who finds herself in a housing predicament because she does not earn enough to be able to afford her independent accommodation.

The authorities earlier this year announced another crackdown on bachelors sharing apartments. According to Dubai Municipality’s rules, bachelors are not allowed to live in residential areas. Under the ‘one villa, one family rule,’ poorer families unable to pay high rents are also limited.

Earlier this year, Dubai’s municipality announced a new crackdown that it called “bachelor eviction drive”, in a bid to move single, low-income workers out of areas deemed for families.

The municipality believes that overcrowding in apartments affects infrastructure, such as sewage pipes, electrical systems, and parking, societal customs and traditions, and excessive wear and tear on properties.

The campaign includes spot checks on homes suspected to contain bachelors — and they, rather thanlandlords, are responsible for paying any resulting fines for overcrowding.

Fines for violators currently stand at Dh10 per square foot of property. The minimum fine is Dh1,000 and the maximum amount is capped at Dh50,000.

Then in August, the municipality ramped up the crackdown, forming a new team of inspectors tasked with touring residential areas during evening hours — when more people are likely to be back in their homes.

The latest figures released by the municipality in August showed that the civic body and Dubai Police conducted 80 inspections targeting bachelors living in residential areas during the first half of 2016. No recent figures were available for inspections related to the “one villa…one family” policy.

But for residents in the lower-income bracket, earning between Dh2,000 and Dh8,000, sharing accommodation is the most viable option. Even for many whose income is more than this, the prospect of sharing accommodation is of appeal as it helps them save more money.

For one Egyptian expat, who did not want to be identified, the high cost of housing has put a damper on his Dubai dream.

In Cairo, his rent for a one-bedroom apartment that was half an hour away from the city’s centre took up one-fifth of what was his equivalent to Dh830 monthly salary.

In Dubai, despite enjoying a far higher income, one-fifth of his Dh5,000 salary buys him only a bedspace located on the edge of Academic City.

“That’s far from downtown, and I don’t get my own place, not even my own room,” he said.

“I’d be much happier in my own private space no matter how small it is than in a shared one.”

In lower-end rent areas in Dubai, mainly Deira, Bur Dubai and Satwa, notices on walls and lamp-posts advertise availability of bed spaces and rooms. There are many factors that drive these offers — coming from the same country — or even region — is usually listed as a precondition to taking the bedspace. Marital status is also a condition.

Privacy with plaster

Bedspaces vary hugely in price. One listing online, which only allows Filipinas, includes high speed internet, cupboard space, and two communal bathrooms, in addition to sleeping space, all for just Dh500 a month.

Some shave down costs even more, by opting to share single beds.

With their small size and harder access, many hopeful tenants prefer standalone, non-bunk beds. For Dh650, a one bedroom apartment in International City includes all utilities and communal use of kitchen crockery and fridge.

Another tier up from a standalone bed is a partitioned room — a space divided by curtains, or, in some cases, covertly installed plasterboard.

The type of tenants desired by bed-space renters are often referred to with euphemisms — an ‘executive bachelor’, for example, refers to a single man who does not work on a building site. A simple ‘bachelor’, on the other hand, usually

refers to a construction worker.

As many people who live in bedspaces have little spare cash for cars, location is key. Most advertisements promise handy access to bus or metro stations.

But while living in a shared apartment is a reality for hundreds of thousands of people in Dubai and other emirates, the practice is often illegal.

In previous decades, rent-controlled housing projects offered affordable living for middle class families. One of these was Shaikh Rashid Colony in Al Karama, built in the late 1970s.

For decades, the colony offered set rents of Dh7,000 per year, a rate that only grew slightly as Dubai’s rents began to skyrocket. But in 2012, the 17-block district — which by then looked to be in advanced stages of ageing — was condemned by Dubai Municipality.

The Filipina teaching assistant employd at a school, who is in her fifties, has little choice but to share home space. She pays Dh800 monthly rent — utilities included — for a space on a bunk bed. To avoid the daily clamber up and down the bunk’s cold metal frame, she pays Dh50 extra for the lower berth.

“My salary is not too high. I have to send money to my family also,” says Marites.

At her school, full-time teachers get free housing provided by the school, a privilege not enjoyed by assistants.

However, though they live in sharing accommodation, Marites and her like do not really enjoy the prospect of sharing a bathroom, washing machine and kitchen with two dozen other people.

Arguments with flatmates take place often.

“Every individual has their own way of life. Sometimes there’s a conflict, but we can handle it,” she says. “You have no choice.’

To make it easier, Marites moved into an apartment occupied only by Filipinas. Living with other nationalities, with different cultural norms and cooking styles, proved to be far less comfortable.

Having a room all to herself is possible, but not practical. Per square foot, single rooms cost far more than entire apartments in the city’s outskirts.

“If you want one room, you have to spend a lot of money, but then you have no salary [left],” she adds.

Marites is just one of hundreds of thousands of Dubai’s residents who finds herself in a housing predicament because she does not earn enough to be able to afford her independent accommodation.

The authorities earlier this year announced another crackdown on bachelors sharing apartments. According to Dubai Municipality’s rules, bachelors are not allowed to live in residential areas. Under the ‘one villa, one family rule,’ poorer families unable to pay high rents are also limited.

Earlier this year, Dubai’s municipality announced a new crackdown that it called “bachelor eviction drive”, in a bid to move single, low-income workers out of areas deemed for families.

The municipality believes that overcrowding in apartments affects infrastructure, such as sewage pipes, electrical systems, and parking, societal customs and traditions, and excessive wear and tear on properties.

The campaign includes spot checks on homes suspected to contain bachelors — and they, rather thanlandlords, are responsible for paying any resulting fines for overcrowding.

Fines for violators currently stand at Dh10 per square foot of property. The minimum fine is Dh1,000 and the maximum amount is capped at Dh50,000.

Then in August, the municipality ramped up the crackdown, forming a new team of inspectors tasked with touring residential areas during evening hours — when more people are likely to be back in their homes.

The latest figures released by the municipality in August showed that the civic body and Dubai Police conducted 80 inspections targeting bachelors living in residential areas during the first half of 2016. No recent figures were available for inspections related to the “one villa…one family” policy.

But for residents in the lower-income bracket, earning between Dh2,000 and Dh8,000, sharing accommodation is the most viable option. Even for many whose income is more than this, the prospect of sharing accommodation is of appeal as it helps them save more money.

For one Egyptian expat, who did not want to be identified, the high cost of housing has put a damper on his Dubai dream.

In Cairo, his rent for a one-bedroom apartment that was half an hour away from the city’s centre took up one-fifth of what was his equivalent to Dh830 monthly salary.

In Dubai, despite enjoying a far higher income, one-fifth of his Dh5,000 salary buys him only a bedspace located on the edge of Academic City.

“That’s far from downtown, and I don’t get my own place, not even my own room,” he said.

“I’d be much happier in my own private space no matter how small it is than in a shared one.”

In lower-end rent areas in Dubai, mainly Deira, Bur Dubai and Satwa, notices on walls and lamp-posts advertise availability of bed spaces and rooms. There are many factors that drive these offers — coming from the same country — or even region — is usually listed as a precondition to taking the bedspace. Marital status is also a condition.

Privacy with plaster

Bedspaces vary hugely in price. One listing online, which only allows Filipinas, includes high speed internet, cupboard space, and two communal bathrooms, in addition to sleeping space, all for just Dh500 a month.

Some shave down costs even more, by opting to share single beds.

With their small size and harder access, many hopeful tenants prefer standalone, non-bunk beds. For Dh650, a one bedroom apartment in International City includes all utilities and communal use of kitchen crockery and fridge.

Another tier up from a standalone bed is a partitioned room — a space divided by curtains, or, in some cases, covertly installed plasterboard.

The type of tenants desired by bed-space renters are often referred to with euphemisms — an ‘executive bachelor’, for example, refers to a single man who does not work on a building site. A simple ‘bachelor’, on the other hand, usually

refers to a construction worker.

As many people who live in bedspaces have little spare cash for cars, location is key. Most advertisements promise handy access to bus or metro stations.

But while living in a shared apartment is a reality for hundreds of thousands of people in Dubai and other emirates, the practice is often illegal.

In previous decades, rent-controlled housing projects offered affordable living for middle class families. One of these was Shaikh Rashid Colony in Al Karama, built in the late 1970s.

For decades, the colony offered set rents of Dh7,000 per year, a rate that only grew slightly as Dubai’s rents began to skyrocket. But in 2012, the 17-block district — which by then looked to be in advanced stages of ageing — was condemned by Dubai Municipality.

Eight years earlier, another colony, Al Ghusais, was torn down. While several colonies still exist, most have not been replaced. In Al Karama, the colony was replaced by shiny — and expensive — new apartment blocks.

And it’s not just apartment blocks filled to the brim with bedspace-dwellers. Last year, the municipality said that in some older areas in Dubai, including Jumeirah 1 and Al Rashidiya, close to 80 per cent of villas were rented out to singles or sharing families.

Trakhees, the separate regulatory authority for freehold areas, including Palm Jumeirah, Jumeirah Lakes Towers, Discovery Gardens and International City, has held campaigns to stop overcrowding in apartments.

Under the rules, each person must get at least 200 square feet from the total property area — an area that covers around eight pool tables. Of the freehold areas, many bed-space dwellers opt for Discovery Gardens and International City.

International City offers affordable bedspaces, with prices starting at around Dh700 per month.

Faced with the expense of living in Dubai, many singles and families have long opted to live in Sharjah or even Ajman, where rents are sometimes half. Yet a trip between emirates that takes just minutes during off-peak times can take hours stuck in bumper-to-bumper traffic.

Some bedspace dwellers can afford far more comfortable options — but say that as they are only in Dubai to send money home, comfort and privacy aren’t priorities.

Diane, who has lived in Dubai for eight years, started work as a receptionist in a marketing company eight years ago, on a salary of Dh3,500. Today, she makes over Dh10,000 a month in a better position, but hasn’t changed her lifestyle.

“We did not come here to have a luxurious life,” says the Filipina.

“When our family back home is suffering, no food, no place, no house, no shelter…[What’s important is to earn] as much as we can earn.”

“That’s why we prefer a bedspace.”

Why Dubai needs lower-cost housing:

In Dubai, where eight out of 10 residents earn less than Dh10,000 a month, many have long chosen to opt for low-cost housing.

But due to high rents, even the cheapest apartments are far out of reach for many residents, who opt for bedspaces and partitioned rooms to cut costs.

That’s one of the reasons why Neil Walmsley, director and Middle East planning leader at Engineering consultancy Arup, recommends developers build cheaper projects.

Over his 11 years working in the UAE, the urban planner has been a consultant on dozens of private and public sector projects in the region.

He advises his clients — many of them large property developers — to include the building of affordable, lower cost properties into their masterplans.

But due to a lack of regulations that ensure low-cost homes are built alongside Dubai’s glitzy high-rises and spacious, landscaped villa complexes, not all developers are interested.

“We can only advise on what we think our clients should consider. We don’t have a mandate to impose something that is not required by the government or aligned with the clients’ objectives,” says Walmsley.

Authorities define middle-income housing as ranging in cost from Dh25,200 to 88,200 per year.

Dubai Municipality rolled out similar proposals to get developers to allocate 15-20 per cent of new projects for affordable projects.

But so far, nothing has been signed into law.

In Dubai, and the rest of the UAE, the large population of expats, many of whom only stay for few years or less, make the country challenging to city planners. For new movers, many of whom take up demanding jobs, there’s little time — or money — to spend hunting for the best place to live.

“The guy who just arrived from his home country, and needs somewhere to stay, will stay where his friend or relative is already staying. He won’t go and find a more affordable, more spacious alternative somewhere else. In that sense, it’s a bit of systematic cultural behaviour pattern that reinforces existing housing types or lifestyle choices.”

Having an affordable public transport network to serve a city’s outskirts could be part of a solution towards putting more affordable homes on the market.

Low-cost housing is most effective when its location enjoys transport connectivity, he said.

A lack of affordable housing in any city will lead to economic consequences, Walmsley warned.

“In general, any rapidly expanding city has to keep up with its operational needs... if it is not financially or socially viable for people to be here to deliver certain roles in the economy, then the economy will suffer, without doubt.”

And it’s not just apartment blocks filled to the brim with bedspace-dwellers. Last year, the municipality said that in some older areas in Dubai, including Jumeirah 1 and Al Rashidiya, close to 80 per cent of villas were rented out to singles or sharing families.

Trakhees, the separate regulatory authority for freehold areas, including Palm Jumeirah, Jumeirah Lakes Towers, Discovery Gardens and International City, has held campaigns to stop overcrowding in apartments.

Under the rules, each person must get at least 200 square feet from the total property area — an area that covers around eight pool tables. Of the freehold areas, many bed-space dwellers opt for Discovery Gardens and International City.

International City offers affordable bedspaces, with prices starting at around Dh700 per month.

Faced with the expense of living in Dubai, many singles and families have long opted to live in Sharjah or even Ajman, where rents are sometimes half. Yet a trip between emirates that takes just minutes during off-peak times can take hours stuck in bumper-to-bumper traffic.

Some bedspace dwellers can afford far more comfortable options — but say that as they are only in Dubai to send money home, comfort and privacy aren’t priorities.

Diane, who has lived in Dubai for eight years, started work as a receptionist in a marketing company eight years ago, on a salary of Dh3,500. Today, she makes over Dh10,000 a month in a better position, but hasn’t changed her lifestyle.

“We did not come here to have a luxurious life,” says the Filipina.

“When our family back home is suffering, no food, no place, no house, no shelter…[What’s important is to earn] as much as we can earn.”

“That’s why we prefer a bedspace.”

Why Dubai needs lower-cost housing:

In Dubai, where eight out of 10 residents earn less than Dh10,000 a month, many have long chosen to opt for low-cost housing.

But due to high rents, even the cheapest apartments are far out of reach for many residents, who opt for bedspaces and partitioned rooms to cut costs.

That’s one of the reasons why Neil Walmsley, director and Middle East planning leader at Engineering consultancy Arup, recommends developers build cheaper projects.

Over his 11 years working in the UAE, the urban planner has been a consultant on dozens of private and public sector projects in the region.

He advises his clients — many of them large property developers — to include the building of affordable, lower cost properties into their masterplans.

But due to a lack of regulations that ensure low-cost homes are built alongside Dubai’s glitzy high-rises and spacious, landscaped villa complexes, not all developers are interested.

“We can only advise on what we think our clients should consider. We don’t have a mandate to impose something that is not required by the government or aligned with the clients’ objectives,” says Walmsley.

Authorities define middle-income housing as ranging in cost from Dh25,200 to 88,200 per year.

Dubai Municipality rolled out similar proposals to get developers to allocate 15-20 per cent of new projects for affordable projects.

But so far, nothing has been signed into law.

In Dubai, and the rest of the UAE, the large population of expats, many of whom only stay for few years or less, make the country challenging to city planners. For new movers, many of whom take up demanding jobs, there’s little time — or money — to spend hunting for the best place to live.

“The guy who just arrived from his home country, and needs somewhere to stay, will stay where his friend or relative is already staying. He won’t go and find a more affordable, more spacious alternative somewhere else. In that sense, it’s a bit of systematic cultural behaviour pattern that reinforces existing housing types or lifestyle choices.”

Having an affordable public transport network to serve a city’s outskirts could be part of a solution towards putting more affordable homes on the market.

Low-cost housing is most effective when its location enjoys transport connectivity, he said.

A lack of affordable housing in any city will lead to economic consequences, Walmsley warned.

“In general, any rapidly expanding city has to keep up with its operational needs... if it is not financially or socially viable for people to be here to deliver certain roles in the economy, then the economy will suffer, without doubt.”

No Comments For This Post, Be first to write a Comment.

Most viewed from International

Most viewed from World

AIMIM News

Latest Urdu News

Most Viewed

May 26, 2020

Do you think Canada-India relations will improve under New PM Mark Carney?

Latest Videos View All

Like Us

Home

About Us

Advertise With Us

All Polls

Epaper Archives

Privacy Policy

Contact Us

Download Etemaad App

© 2025 Etemaad Daily News, All Rights Reserved.

.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)