Saudi Arabia Is Fast Losing Allies

Sat 22 Oct 2016, 14:26:16

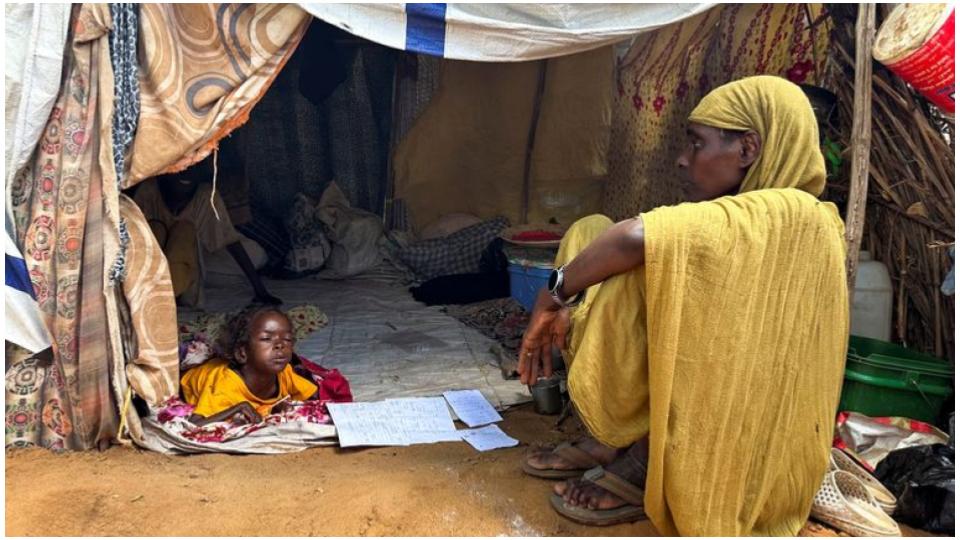

After the Saudi-led airstrikes on Sanaa, Yemen’s capital, on October 8, pressure on Western nations selling weapons to Saudi Arabia will be mounting . Recently, the United States Congress passed into law the Justice Against State Sponsors of Terrorism (JASTA) bill, aimed at the Kingdom of Saudi Arabia (KSA). These are the two latest signs that the KSA is becoming a little more isolated and losing some crucial allies.

The uproar in the West against the selling of weapons to the KSA has been growing louder, particularly in light of the escalating Yemen campaign. From Canada under fire for a 2014 $15 billion contract—that the government said it won’t cancel—to Sweden cutting off military cooperation that had been going on since 2005, to the UK, where talk of halting arms exports if humanitarian laws are broken in Yemen. In light of the historically close relationship with the UK, Saudi Arabia didn’t take these threats well: for proof, the Saudi Ambassador in London hinted that there could be less co-operation on terrorism and a possible reduction of contracts and investments.

The situation is serious because even the United States takes a tough stance on the KSA. The Kingdom understands this and has hired five additional lobbying firms in Washington, DC since September to defend its interests in the U.S. and alter its image. Whether a PR stunt or a real change of heart, Saudis have acknowledged they misled the West regarding funding terrorism. In the meantime, the KSA is pondering if and how to retaliate: will it make good on its threat to sell hundreds of billions of dollars of U.S. assets ?

This unfavorable treatment of Saudi Arabia would have been utterly unthinkable just even two years ago.

The Obama Administration’s decision and strategy to pivot toward the Shia world and Iran have left the KSA in the dust. It looks like archenemy Iran has won the public relations war against Saudi Arabia—at least in the West. Iran, all of a sudden, became the nice kid on the block because of the nuclear deal. Saudi Arabia became the bad one. Proof of this: After 15 years of preventing the publication of the 28 pages pertaining to the KSA in the 9/11 Commission report, the U.S. finally yielded. An additional sign of the meltdown in U. S. -KSA relations is that it took a full six weeks in February 2016

ginger_software_uiphraseguid="2b057de7-c07e-446e-a1b5-890ddc46bf58" class="GINGER_SOFTWARE_mark">for

ginger_software_uiphraseguid="2b057de7-c07e-446e-a1b5-890ddc46bf58" class="GINGER_SOFTWARE_mark">for

The West isn’t the only one distancing itself from Saudi Arabia. In fact, tensions with close allies have increased since the arrival to power of King Salman in January 2015. The main contention point is the renewed support of the kingdom to the Muslim Brotherhood and some Salafi-Jihadi groups. First, the rapprochement with the Muslim Brotherhood is driving a wedge with both the UAE and Egypt. Both countries view the Muslim Brotherhood as a mortal danger. A new lenient policy toward the Muslim Brotherhood under King Salman is all the more bizarre, given that the organization is still on the list of terrorist groups in Saudi Arabia. Also, Saudi Arabia has been the destination of choice for Muslim Brotherhood leaders such as Hamas’ Khaled Meshaal, Tunisia’s Rachid Ghanouchi, Jordan’s Said and Yemen’s al Zindani.

Second and even more problematic is the alleged funding and material help Saudi Arabia is providing to the ex/present/future al-Qaeda franchise in Syria, the former al Nusra front. This de facto alliance is something against nature since one of al Qaeda’s main enemies remain the Saudi regime. This fits in a new realpolitik from Riyadh that has embraced the Middle East policy that the enemy of my enemy is my friend. In Syria, Assad is much more of an enemy than al-Qaeda.

That this policy has angered several of Riyadh’s classical allies—and Al Nusra has supposedly cut the cord with al-Qaeda—is not changing anything.

The most hurtful recent challenge to Saudi Arabia’s status took place at a UAE-financed worldwide conference of Sunni religious figures that included leaders such as Cairo’s Al Azhar imam. The clerics concluded that Wahhabism—the principal tenet of the Saudi regime—was not part of Sunni Islam. This is very significant because it is jeopardizing Saudi’s legitimacy as the Custodian of Islam’s holiest sites.

Pakistan, another historical ally of Saudi Arabia, is also turning its back. Indeed, despite the huge Saudi investments including allegedly financing Pakistan’s nuclear program, Pakistan has refused to send soldiers in Yemen to participate in the Saudi-led coalition and also didn’t take part in the large Muslim anti-Islamic State coalition.

While on the surface Saudi Arabia’s position has been stable, there is a growing opposition to the country in the West and even from allies in the Muslim world. For example, the relations with Egypt have dramatically worsened in the past few weeks, after Egypt backstabbed Saudi Arabia by voting in favor of a United Nations resolution on Syria put forth by Russia and the KSA retaliated by suspending the supply of oil product. Two days later, Saudi Arabia made a $2 billion payment to bail out Egypt, which shows that RealPolitik prevailed in the end…

No Comments For This Post, Be first to write a Comment.

Most viewed from International

Most viewed from World

AIMIM News

Latest Urdu News

Most Viewed

May 26, 2020

Do you think Canada-India relations will improve under New PM Mark Carney?

Latest Videos View All

Like Us

Home

About Us

Advertise With Us

All Polls

Epaper Archives

Privacy Policy

Contact Us

Download Etemaad App

© 2025 Etemaad Daily News, All Rights Reserved.

.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)