Uganda is shutting down schools funded by Mark Zuckerberg, Bill Gates

Fri 25 Nov 2016, 23:42:48

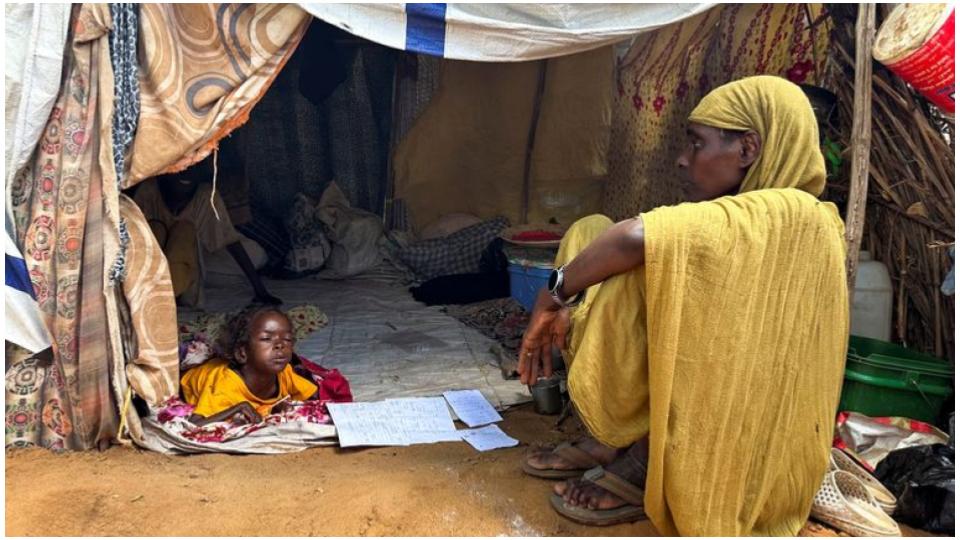

A legal tug-of-war between Ugandan authorities and a for-profit international chain of schools has led to the education provider being ordered to shut down in a matter of weeks, leaving the lives of thousands of pupils in limbo.

Uganda's High Court has described the Bridge International Academies (BIA) -- which is funded by the likes of Microsoft's Bill Gates and Facebook's Mark Zuckerberg -- as unsanitary and unqualified, and has ordered it to close its doors in December because it ignored Uganda's national standards and put the "life and safety" of its 12,000 young students on the line.

The Director of Education Standards for the Ministry, Huzaifa Mutazindwa, told CNN that the nursery and primary schools were not licensed, the teachers weren't qualified and that there was no record of its curriculum being approved.

"The Ministry does not know what is being taught in these schools which is a point of concern to (the) government," Mutazindwa said.

The low-cost education provider, which has 63 campuses across Uganda, is allowed to remain open until December 8 to allow students to sit for exams and finish third term. This was after BIA secured an interim court order that restrained the government from closing its schools until its main case for stay could be heard in court.

For its part, BIA — which runs more than 400 nursery and primary schools across Africa — has continuously denied the allegations that have been made by the government.

"There's a lot of miscommunication and a lot of very serious, unfounded allegations. We would like to be given the opportunity to explain ourselves ... The Ministry has been unwilling to give us an audience to set the record straight," Uganda's BIA director, Andrew White, told CNN.

In a statement, BIA addressed eight allegations that have been made about its operations. It said it teaches the Ugandan curriculum, all schools have good sanitation facilities and that the majority of their teachers are certified and registered. Those who aren't certified and registered, it said, are attending in-service training.

Pupils from Bridge International Academies protest after Uganda's High Court ordered the closure of its low-cost private schools.

Pupils from Bridge International Academies protest after Uganda's High Court ordered the closure of its low-cost private schools.

When asked why the allegations were made if they weren't true, White said: "We definitely feel like a lot of pressure has been applied to have a particular view of Bridge that is a negative one."

He suggested that the opposition against BIA was because the campuses competed against local state-run and private schools.

"I don't think the government is threatened by Bridge, but I think lobby groups are trying to make the government and ministry feel like they should be," White said.

A private institution 'profiting from the poor'

One educational advocacy group agrees with the Ugandan authorities' decision to close BIA.

President of the Global Campaign for Education (GCE), Camilla Croso, told CNN that the quality of their schools is "totally inadequate and unacceptable."

"They are profit making enormously," she said. "It's very indecent because they are looking at poor people as a profitable market."

"It really is incompatible to have human rights and profit making because you are motivated and act in completely different ways."

Almost 20% of Uganda's population live below the poverty line, according to The World Bank.

Salima Namusobya, the Executive Director for the Initiative for Society and Economic Rights (ISER), also agreed with the closure and told CNN that BIA's intentions were insincere.

"(BIA) has come into the country and not discussed with the regulators and set up a massive project," she said, adding that privatization of education goes against human rights principles -- particularly if it targets the poor.

"I think there's some level of arrogance that comes with this and I really think they're for the profit and not to assist the children."

'Standardized' and 'scripted' education

Critics allege that BIA's education methods are not transparent, and that their approach is standardized and scripted.

"You can't call it an education

that Bridge is offering," Croso said.

that Bridge is offering," Croso said.

"You have technology -- like tablets -- often standing in place of teachers and you have very scripted classes that tell the teachers exactly what to do and when -- so you don't have any sort of autonomy and you can't improvise."

She said teachers needed to understand the topics so they could panel it.

"Education has nothing to do with that (standardization) -- it's about debating, thinking and discussions."

Croso said that instead, society should demand that governments "step into their responsibility" to ensure it is putting resources into quality education.

Namusobya from ISER said she believes BIA causes segregation between the poor and rich.

She said in government-run schools every child is treated equally, but BIA's model only targets the poor.

"(They are) only going to interact with themselves... When will they get to interact with other children?

"It's like you're saying that these children, because they are poor, they deserve to be in bad infrastructure, they deserve to sit in classes on their own and maybe one day they'll catch up with the rich."

There's no 'adequate choice of education' in Uganda

In response to the criticism it's received, BIA argues that it provides alternative education for students who would other be forced to study in state-run schools and notes that it only charges $6 a month.

"The existence of Bridge is in response to hundreds of thousands of parents who as of today don't have an adequate choice of education for their children," White said.

"The reason Bridge exists is to try and help the government address this by providing innovative and cost effective solutions."

While $6 a month seems like a minute amount to some, NGOs have argued that it's a substantial amount to charge those in poverty.

But White said BIA provides an "effective and affordable service" that parents want for their children.

"The poor are individual actors who can make informed decisions on how to spend their hard earned money," he said.

"Parents have seen in the short time that their children have been with Bridge that they are incredibly engaged. Parents for the first time see their kids wanting to go to school and they have children who are actively doing their homework every day."

While BIA has not yet evaluated the performance of their children in Uganda, in Kenya BIA found that is students "outperform their peers in public schools in basic literacy and reading."

"We have a track record for academic success ... The model is very similar in Uganda and we expect in 2017 they will also excel." White said.

He said BIA uses technology to help its teachers provide a "holistic" education.

"Bridge does not believe technology can replace a teacher ... We've spent millions of dollars to ensure our teachers have the resources and skills to make sure they can provide our pupils with the highest possible education."

He said if those lobbying against the organization "came and engaged" with their teaching and learning they "would see that it is extremely interactive" where teachers engaged with their pupils and worked equally as hard on the strong and weak performers.

Co-Founder of BIA, Shannon May, also explained to CNN how its school fees and donations were invested into the academies.

"All school fees are spent on operating and supporting the academies," she said.

"In addition, Bridge has invested over $100m in education and technology research and development, capital expenses for schools, and to cover operating expenses that are greater than the fees we charge."

But Croso from GCE said that regardless, for BIA and any other private organization to benefit Ugandan education, they need to work within the country's law.

"BIA stands out and this is an opportunity to learn from the mistakes," she said.

While the debate continues in Uganda until the final hearing in December, White from BIA said it was "affirming" to see how committed parents were to BIA in the short time they had children in their classes.

"What we're doing in Uganda is positive. We can see the impact it's having and we want to continue to do whatever we can and whatever is in our power to make sure that continues."

No Comments For This Post, Be first to write a Comment.

Most viewed from International

Most viewed from World

AIMIM News

Latest Urdu News

Most Viewed

May 26, 2020

Do you think Canada-India relations will improve under New PM Mark Carney?

Latest Videos View All

Like Us

Home

About Us

Advertise With Us

All Polls

Epaper Archives

Privacy Policy

Contact Us

Download Etemaad App

© 2025 Etemaad Daily News, All Rights Reserved.

.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)