Why scientists created the world's smallest house

Wed 30 May 2018, 14:48:23

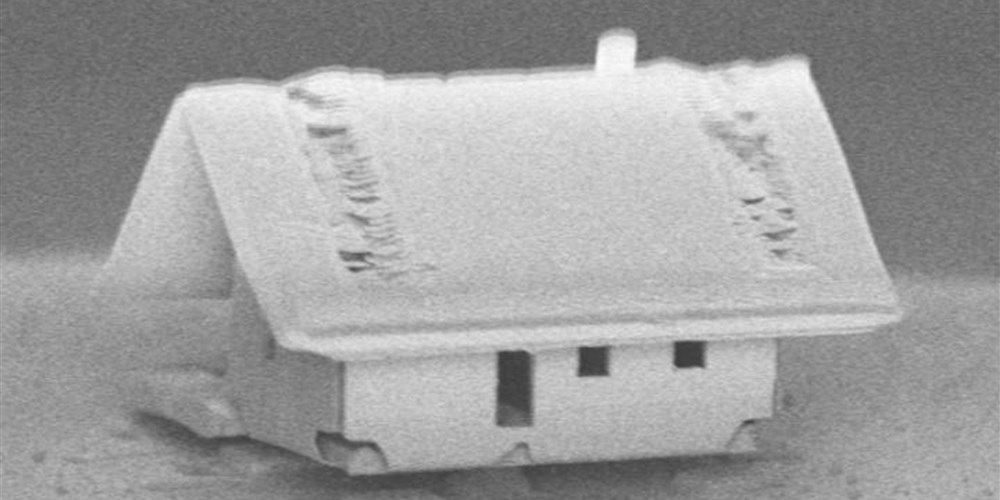

It’s the tiny house movement taken to extremes: Scientists in France have fabricated a single-story home that measures only 20 microns (millionths of a meter) across. That’s about one-fifth the width of a human hair, or roughly 500,000 times smaller than a human-scaled two-story house.

The minuscule house features a tiled roof, seven windows, a door and a teensy chimney. It was created at the Femto-ST Institute in Besançon by a robot controlling a tightly focused beam of charged particles known as ions.

The micro-dwelling was built inside a vacuum chamber to demonstrate the dexterity and precision of the team's robotic system. But the project was more than just a chance to show off. The scientists say the capability to create such intricate nanostructures could one day transform industries ranging from aerospace to medicine.

“In the future, we want to develop this type of nanofactory in order to be able to reduce the size of a lot of objects that we use today,” Jean-Yves Rauch, an engineer at the institute and co-author of a new paper about the feat published recently in the Journal of Vacuum Science and Technology A, told NBC News MACH in an

email.

email.

The robot started with a layer of silica, the main component of sand, and used the ion beam to shape the walls and cut out the windows and door. To assemble the walls, the robot used the beam to score the silica without cutting all the way through, Rauch said, and then the structure was folded into place like origami.

Mark Swihart, a professor of chemical and biological engineering at the University of Buffalo who wasn't involved in the effort, called the demonstration “quite impressive,” adding that the fabrication method used to build the house pushes existing technology “in a new way to enable creation of microstructures that could not be realized before.”

Rauch said he and his colleagues will attempt to fabricate even smaller structures, and eventually hope to create minute biosensors on the tips of optical fibers that could measure temperature and other conditions in difficult-to-access places and could even perform more complex tasks such as detecting viruses in blood vessels.

“We are not working in a new field of research," Rauch said, "but we are constantly seeking to push the limits of assembly precision and measurement precision."

No Comments For This Post, Be first to write a Comment.

Most viewed from International

Most viewed from World

AIMIM News

Latest Urdu News

Most Viewed

May 26, 2020

Do you think Canada-India relations will improve under New PM Mark Carney?

Latest Videos View All

Like Us

Home

About Us

Advertise With Us

All Polls

Epaper Archives

Privacy Policy

Contact Us

Download Etemaad App

© 2025 Etemaad Daily News, All Rights Reserved.

.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)