India raises withdrawal limit as rupee anger mounts

Mon 14 Nov 2016, 22:31:14

The Indian government has raised the limit on cash withdrawals following widespread public anger about the surprise abolition of 500 ($7.60; £5.90) and 1,000 rupee notes last week.

Customers can now withdraw up to 2,500 rupees a day from cash machines, rather than 2,000, the finance ministry said.

Many cash machines are not working because they have not been adapted for the new 500 and 2,000 rupee notes.

Long queues at many banks were making it difficult to make withdrawals.

The government said Indian banks had received 3 trillion rupees ($44bn; £35bn) of large denomination notes since the move was announced on Tuesday night.

How India's currency ban is hurting the poor

Desperate housewives' scramble to swap secret savings

'No customers': Indians react to currency ban

Holders of notes abroad face tough battle

Can currency ban really curb black economy?

The money no one will take

The abolition of the 500 and 1,000 rupee notes is intended to crack down on corruption and bring cash worth billions of dollars in unaccounted wealth back into the economy.

The two notes accounted for more than four fifths of the currency in circulation and the change threatens to disrupt much of India's cash-driven economy.

The government has also relaxed withdrawal limits from banks, removing the 10,000 rupees a day restriction and increasing the weekly

limit by 4,000 rupees to 24,000.

The Reserve Bank of India urged people not to hoard cash, adding that rupees were available "when they need it".

It has asked banks to report daily rather than fortnightly the amount of cash withdrawn and exchanged to give a more accurate picture of circulation.

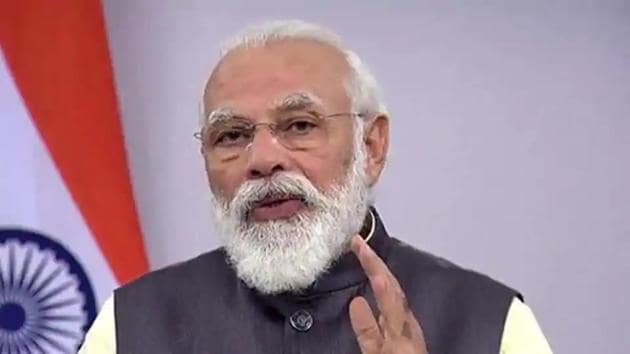

Prime Minister Narendra Modi acknowledged the "pain" being experienced by millions but said the scheme was "not born from arrogance".

"This hardship is only for 50 days," he said in a speech in Goa on Sunday. "Please, 50 days, just give me 50 days. After 30 December, I promise to show you the India that you have always wished for."

Indians have until 30 December to exchange the now-defunct notes at banks.

Since being elected in 2014, Mr Modi has pledged to crack down on "black money" kept hidden from authorities. The "black economy" could account for about a fifth of India's GDP, according to investment firm Ambit.

His political opponents said they would unite to fight the abolition of the high denomination notes, which has made lives difficult for millions of ordinary people - particularly those without bank accounts who keep their savings in cash.

Mulayam Singh Yadav, leader of Samajwadi party, called on the prime minister to reverse his decision.

"The government has spread anarchy in the country, the common man cannot buy daily products," Mr Yadav said.

Customers can now withdraw up to 2,500 rupees a day from cash machines, rather than 2,000, the finance ministry said.

Many cash machines are not working because they have not been adapted for the new 500 and 2,000 rupee notes.

Long queues at many banks were making it difficult to make withdrawals.

The government said Indian banks had received 3 trillion rupees ($44bn; £35bn) of large denomination notes since the move was announced on Tuesday night.

How India's currency ban is hurting the poor

Desperate housewives' scramble to swap secret savings

'No customers': Indians react to currency ban

Holders of notes abroad face tough battle

Can currency ban really curb black economy?

The money no one will take

The abolition of the 500 and 1,000 rupee notes is intended to crack down on corruption and bring cash worth billions of dollars in unaccounted wealth back into the economy.

The two notes accounted for more than four fifths of the currency in circulation and the change threatens to disrupt much of India's cash-driven economy.

The government has also relaxed withdrawal limits from banks, removing the 10,000 rupees a day restriction and increasing the weekly

limit by 4,000 rupees to 24,000.

The Reserve Bank of India urged people not to hoard cash, adding that rupees were available "when they need it".

It has asked banks to report daily rather than fortnightly the amount of cash withdrawn and exchanged to give a more accurate picture of circulation.

Prime Minister Narendra Modi acknowledged the "pain" being experienced by millions but said the scheme was "not born from arrogance".

"This hardship is only for 50 days," he said in a speech in Goa on Sunday. "Please, 50 days, just give me 50 days. After 30 December, I promise to show you the India that you have always wished for."

Indians have until 30 December to exchange the now-defunct notes at banks.

Since being elected in 2014, Mr Modi has pledged to crack down on "black money" kept hidden from authorities. The "black economy" could account for about a fifth of India's GDP, according to investment firm Ambit.

His political opponents said they would unite to fight the abolition of the high denomination notes, which has made lives difficult for millions of ordinary people - particularly those without bank accounts who keep their savings in cash.

Mulayam Singh Yadav, leader of Samajwadi party, called on the prime minister to reverse his decision.

"The government has spread anarchy in the country, the common man cannot buy daily products," Mr Yadav said.

No Comments For This Post, Be first to write a Comment.

Most viewed from National

Most viewed from World

AIMIM News

Latest Urdu News

Most Viewed

May 26, 2020

Which Cricket team will win the IPL 2025 trophy?

Latest Videos View All

Like Us

Home

About Us

Advertise With Us

All Polls

Epaper Archives

Privacy Policy

Contact Us

Download Etemaad App

© 2025 Etemaad Daily News, All Rights Reserved.

.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)