Hiroshima still scarred after seven decades

Thu 06 Aug 2015, 11:17:12

Hiroshima (Japan): Charred bodies bobbed in the brackish waters that flowed through Hiroshima 70 years ago this week, after a once-vibrant Japanese city was consumed by the searing heat of the world's first nuclear attack.

The smell of burned flesh filled the air as scores of survivors with severe burns dived into rivers to escape the inferno. Countless hundreds never emerged, pushed under the surface by the mass of desperate humanity.

"It was a white, silvery flash," said Sunao Tsuboi, 90, of the moment when the United States unleashed what was then the most destructive weapon ever produced.

"I don't know why I survived and lived this long," said Tsuboi. "The more I think about it, the more painful it becomes to recall."

Seven decades since the attack, the city of 1.2 million people is once again thriving as a commercial hub, but the scars of the bombing - physical and emotional - still remain.

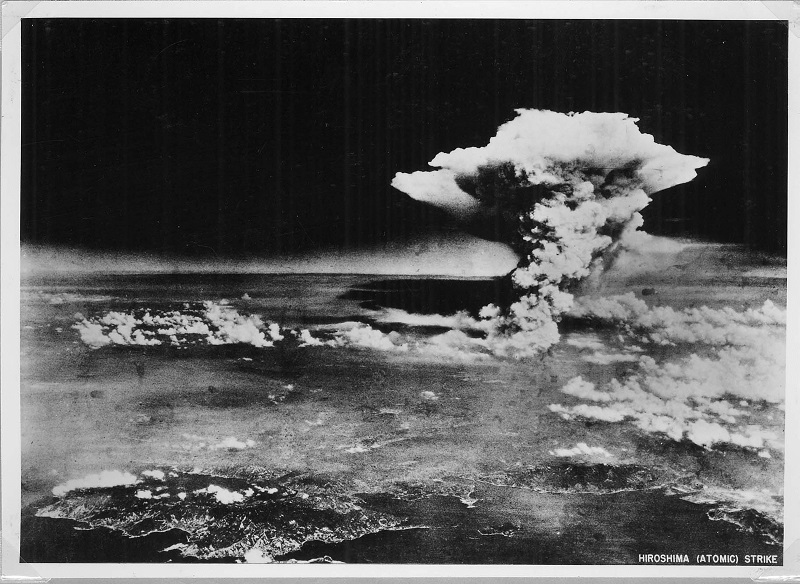

It was 8:15 am on August 6, 1945, when a B-29 bomber called Enola Gay flying high over the city released Little Boy, a uranium bomb with a destructive force equivalent to 16 kilotons of TNT.

Just 43 seconds later, when it was 600 metres from the ground, it erupted into a blistering fireball burning at a million degrees Celsius.

Nearly everything around it was incinerated, with the ground level hit by a wall of heat up to 4,000 degrees Celsius - hot enough to melt steel.

Stone buildings survived, but bore the shadows of anything - or anyone - charred in front of them.

Gusts of around 1.5 km a second roared outwards carrying with

them shattered debris, and packing enough force to rip limbs and organs from bodies. The air pressure suddenly dropped due to the blast, crushing those on the ground, and an ominous mushroom cloud rose, towering 16 km above the city.

them shattered debris, and packing enough force to rip limbs and organs from bodies. The air pressure suddenly dropped due to the blast, crushing those on the ground, and an ominous mushroom cloud rose, towering 16 km above the city.

About 140,000 people are estimated to have been killed in the attack, including those who survived the bombing itself but died soon afterwards due to severe radiation exposure.

Tsuboi, then a college student, was about 1.2 km from the hypocentre and was literally blown away by the blast and blinding heat. When he picked himself up, his shirt, trousers and skin flapped from his burned body; blood vessels dangled from open wounds and parts of his ears were missing.

Tsuboi remembers seeing a teenage girl with her right eyeball hanging from her face. Nearby, a woman grasped at her torso in a futile attempt to stop her intestines from falling through a gaping hole.

"There were bodies all over the place," he said. "Ones with no limbs, all charred. I said to myself: 'Are they human?'"

For those that survived, there was the terrifying unknown of radiation sickness still to come. Gums bled, teeth fell out, hair came off in clumps; there were cancers, premature births, malformed babies and sudden deaths.

As tales of the new, unknown illness spread through the war-ravaged country, survivors were shunned out of fear they might bring infection. For years afterwards, many found it difficult to get jobs or marry.

Even today, 70 years on, some "hibakusha" (nuclear survivors) avoid talking openly about their experience for fear of discrimination.

No Comments For This Post, Be first to write a Comment.

Most viewed from Specials

Most viewed from World

AIMIM News

Latest Urdu News

Most Viewed

May 26, 2020

Do you think Canada-India relations will improve under New PM Mark Carney?

Latest Videos View All

Like Us

Home

About Us

Advertise With Us

All Polls

Epaper Archives

Privacy Policy

Contact Us

Download Etemaad App

© 2025 Etemaad Daily News, All Rights Reserved.