How Titanoboa, the 40-Foot-Long Snake, Was Found

Mon 31 Oct 2016, 12:09:45

In Colombia, the fossil of a gargantuan snake has stunned scientists, forcing them to rethink the nature of prehistoric life

In the lowland tropics of northern Colombia, 60 miles from the Caribbean coast, Cerrejón is an empty, forbidding, seemingly endless horizon of dusty outback, stripped of vegetation and crisscrossed with dirt roads that lead to enormous pits 15 miles in circumference. It is one of the world’s largest coal operations, covering an area larger than Washington, D.C. and employing some 10,000 workers. The multinational corporation that runs the mine, Carbones del Cerrejón Limited, extracted 31.5 million tons of coal last year alone.

Cerrejón also happens to be one of the world’s richest, most important fossil deposits, providing scientists with a unique snapshot of the geological moment when the dinosaurs had just disappeared and a new environment was emerging. “Cerrejón is the best, and probably the only, window on a complete ancient tropical ecosystem anywhere in the world,” said Carlos Jaramillo, a paleontologist at the Smithsonian Tropical Research Institute. “The plants, the animals, everything. We have it all, and you can’t find it anywhere else in the tropics.”

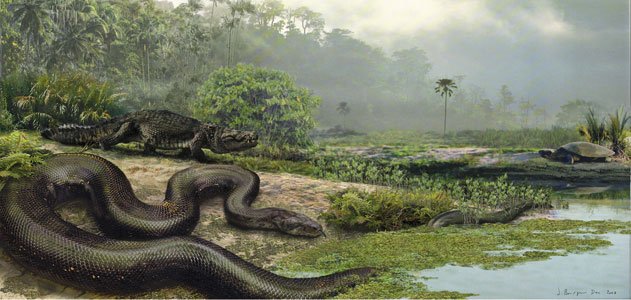

Fifty-eight million years ago, a few million years after the fall of the dinosaurs, Cerrejón was an immense, swampy jungle where everything was hotter, wetter and bigger than it is today. The trees had wider leaves, indicating greater precipitation—more than 150 inches of rain per year, compared with 80 inches for the Amazon now. Mean temperatures may have hovered in the mid- to high-80s Fahrenheit or higher. Deep water from north-flowing rivers swirled around stands of palm trees, hardwoods, occasional hummocks of earth and decaying vegetation. Mud from the flood plain periodically coated, covered and compressed the dead leaves, branches and animal carcasses in steaming layers of decomposing muck dozens of feet thick.

The river basin held turtles with shells twice the size of manhole covers and crocodile kin—at least three different species—more than a dozen feet long. And there were seven-foot-long lungfish, two to three times the size of their modern Amazon cousins.

The lord of this jungle was a truly spectacular creature—a snake more than 40 feet long and weighing more than a ton. This giant serpent looked something like a modern-day boa constrictor, but behaved more like today’s water-dwelling anaconda. It was a swamp denizen and a fearsome predator, able to eat any animal that caught its eye. The thickest part of its body would be nearly as high as a man’s waist. Scientists call

it Titanoboa cerrejonensis.

it Titanoboa cerrejonensis.

It was the largest snake ever, and if its astounding size alone wasn’t enough to dazzle the most sunburned fossil hunter, the fact of its existence may have implications for understanding the history of life on earth and possibly even for anticipating the future.

Titanoboa is now the star of “Titanoboa: Monster Snake,” premiering April 1 on the Smithsonian Channel. Research on the snake and its environment continues, and I caught up with the Titanoboa team during the 2011 field season.

Jonathan Bloch, a University of Florida paleontologist, and Jason Head, a paleontologist at the University of Nebraska, were crouched beneath a relentless tropical sun examining a set of Titanoboa remains with a Smithsonian Institution intern named Jorge Moreno-Bernal, who had discovered the fossil a few weeks earlier. All three were slathered with sunblock and carried heavy water bottles. They wore long-sleeved shirts and tramped around in heavy hiking boots on the shadeless moonscape whose ground cover was shaved away years ago by machinery.

“It’s probably an animal in the 30- to 35-foot range,” Bloch said of the new find, but size was not what he was thinking about. What had Bloch’s stomach aflutter on this brilliant Caribbean forenoon was lying in the shale five feet away.

“You just never find a snake skull, and we have one,” Bloch said. Snake skulls are made of several delicate bones that are not very well fused together. “When the animal dies, the skull falls apart,” Bloch explained. “The bones get lost.”

The snake skull embraced by the Cerrejón shale mudstone was a piece of Titanoboa that Bloch, Head and their colleagues had been hoping to find for years. “It offers a whole new set of characteristics,” Bloch said. The skull will enhance researchers’ ability to compare Titanoboa to other snakes and figure out where it sits on the evolutionary tree. It will provide further information about its size and what it ate.

Even better, added Head, gesturing at the skeleton lying at his feet, “our hypothesis is that the skull matches the skeleton. We think it’s one animal.”

Looking around the colossal mine, evidence of an ancient wilderness can be seen everywhere. Every time another feet-thick vein of coal is trucked away, an underlayer of mudstone is left behind, rich in the fossils of exotic leaves and plants and in the bones of fabulous creatures.

“When I find something good, it’s a biological reaction,” said Bloch. “It starts in my stomach.”

No Comments For This Post, Be first to write a Comment.

Most viewed from Specials

Most viewed from World

AIMIM News

Latest Urdu News

Most Viewed

May 26, 2020

Do you think Canada-India relations will improve under New PM Mark Carney?

Latest Videos View All

Like Us

Home

About Us

Advertise With Us

All Polls

Epaper Archives

Privacy Policy

Contact Us

Download Etemaad App

© 2025 Etemaad Daily News, All Rights Reserved.

.jpg)

.jpg)